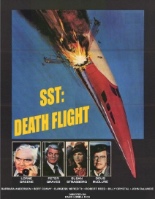

Things are not going well for Cutlass Aircraft Maiden One. The supersonic transport jet’s media circus of an experiment flight from New York to Paris has been sabotaged; a Third World flu virus has been loosed onboard; and, dammit, who the hell let Bert Convy on this plane?

Things are not going well for Cutlass Aircraft Maiden One. The supersonic transport jet’s media circus of an experiment flight from New York to Paris has been sabotaged; a Third World flu virus has been loosed onboard; and, dammit, who the hell let Bert Convy on this plane?

Welcome, disaster-flick junkies, to SST: Death Flight, a made-for-TV Airport rip-off so blatant that it earned director David Lowell Rich the plum gig of guiding the final Airport sequel, The Concorde … Airport ’79, off the tarmac.

Piloted by testy Capt. Walsh (Robert Reed, TV’s Brady Bunch patriarch), America’s first SST passenger jet flies the friendly skies while breaking the sound barrier. Everyone who’s anyone has secured a seat on the transatlantic flight: the governor, some contest winners, a former pilot who might possibly come in handy (Doug McClure, Satan’s Triangle), a World Health Organization doctor (Brock Peters, Two-Minute Warning) and a busty beauty queen (Misty Rowe, Meatballs Part II) who talks about how she’s been farting all day. Taking the thankless roles of flight attendants are Tina Louise (TV’s Gilligan’s Island) and Billy Crystal (presumably auditioning for TV’s Soap).

Piloted by testy Capt. Walsh (Robert Reed, TV’s Brady Bunch patriarch), America’s first SST passenger jet flies the friendly skies while breaking the sound barrier. Everyone who’s anyone has secured a seat on the transatlantic flight: the governor, some contest winners, a former pilot who might possibly come in handy (Doug McClure, Satan’s Triangle), a World Health Organization doctor (Brock Peters, Two-Minute Warning) and a busty beauty queen (Misty Rowe, Meatballs Part II) who talks about how she’s been farting all day. Taking the thankless roles of flight attendants are Tina Louise (TV’s Gilligan’s Island) and Billy Crystal (presumably auditioning for TV’s Soap).

There’s also a very angry Cutlass engineer (George Maharis, Murder on Flight 502) whom the powers that be turned down for a promotion, so he switches a barrel of Maiden One’s hydraulic fluid for one filled with laundry detergent … and still boards the doomed flight — a pretty stupid move, if you ask me, but that’s how these things roll. Same goes for casting Convy as a heel, as any viewer of the Irwin Allen telepic Hanging by a Thread could tell you. In a scene added for SST’s European theatrical release (and intact on DVD), his curly-headed cad of a character keeps yanking down the spaghetti straps of Rowe’s dress in order to free her breasts and join the mile-high club.

When the effed-with barrel springs a leak, the resulting spill looks like tomato soup. When the plane is shown in flight, it looks like a Matchbox toy being held in frame by the tail. And when SST: Death Flight plays, it does indeed look like an Airport sequel, starting with 99 problems and right down to an overstuffed cast, including Peter Graves, Burgess Meredith, Lorne Greene and Regis Philbin. —Rod Lott

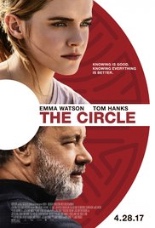

Bailey’s latest baby is SeeChange, all-seeing cameras embedded in sleek spheres the size of cat’s-eye marbles; because of their portability and line of camouflaged colors, SeeChange cams are ideal for global “accountability.” Mae becomes something of a cause célèbre when she agrees to wear one and live a life of a broadband-broadcast transparency 24/7 (with three-minute breaks to heed nature’s call). Then Bailey releases software that allows SeeChange users to find anyone anywhere in the world in the matter of minutes — crowd-sourced bounty hunting, if you will. Raise your hand if you think Very Bad Things will come of this.

Bailey’s latest baby is SeeChange, all-seeing cameras embedded in sleek spheres the size of cat’s-eye marbles; because of their portability and line of camouflaged colors, SeeChange cams are ideal for global “accountability.” Mae becomes something of a cause célèbre when she agrees to wear one and live a life of a broadband-broadcast transparency 24/7 (with three-minute breaks to heed nature’s call). Then Bailey releases software that allows SeeChange users to find anyone anywhere in the world in the matter of minutes — crowd-sourced bounty hunting, if you will. Raise your hand if you think Very Bad Things will come of this.  In past films —

In past films —

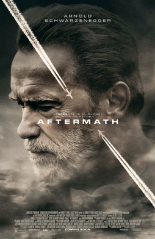

But every tragedy needs a villain’s face, and Roman is intent on hunting Jake down to confront him and demand the apology he has received from no one. Meanwhile, the weight of reality bears heavily on Jake’s shoulders, threatening to tear his family asunder as well. (Perennial

But every tragedy needs a villain’s face, and Roman is intent on hunting Jake down to confront him and demand the apology he has received from no one. Meanwhile, the weight of reality bears heavily on Jake’s shoulders, threatening to tear his family asunder as well. (Perennial