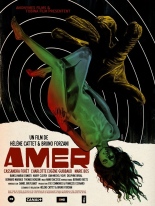

If you have a hard-on for the works of Mario Bava and Dario Argento, you’ll love Amer, a quasi-anthology French film that pays tribute to those Italian masters. While the giallo celebration’s title translates to “bitter,” Amer is oh-so-sweet, a thrilling debut from filmmakers Hélenè Cattet and Bruno Forzani. Does it hurt that it contains the best visual representation of an orgasm I’ve ever seen? Aucun.

If you have a hard-on for the works of Mario Bava and Dario Argento, you’ll love Amer, a quasi-anthology French film that pays tribute to those Italian masters. While the giallo celebration’s title translates to “bitter,” Amer is oh-so-sweet, a thrilling debut from filmmakers Hélenè Cattet and Bruno Forzani. Does it hurt that it contains the best visual representation of an orgasm I’ve ever seen? Aucun.

The movie is comprised of three chapters in the life of Ana, first as an only child (Cassandra Forêt) who lives in a lakeside mansion with her parents and an elderly housekeeper they suspect of being a witch. Told with an array of eyeballs and keyholes in extreme close-ups, it’s the most overtly horror portion, imparting a strong, unsettling vibe reminiscent of the “Drop of Water” segment from Bava’s Black Sabbath.

The middle (and shortest) part of Amer finds Ana as an adolescent (Charlotte Eugène Guibbaud) with bee-stung lips and a budding sexuality that threatens to turn into danger, as she accompanies her mother (Bianca Maria D’Amato) on a walk into the dizzying, labyrinthian cobblestone streets of the nearby village. By the final tale, Ana is a full-blown gorgeous woman (Marie Bos) returning to her childhood home now abandoned and in disrepair … and complete with one of those black-gloved, razor-wielding psychos on the grounds.

The middle (and shortest) part of Amer finds Ana as an adolescent (Charlotte Eugène Guibbaud) with bee-stung lips and a budding sexuality that threatens to turn into danger, as she accompanies her mother (Bianca Maria D’Amato) on a walk into the dizzying, labyrinthian cobblestone streets of the nearby village. By the final tale, Ana is a full-blown gorgeous woman (Marie Bos) returning to her childhood home now abandoned and in disrepair … and complete with one of those black-gloved, razor-wielding psychos on the grounds.

If the music score sounds spot-on, it should, sporting ’70s cuts from Ennio Morricone, Bruno Nicolai and Stelvio Cipriani, putting it squarely at the head of the class of giallo grad school. Amer may baffle those whose viewing habits don’t cross oceans, but I found it absolutely absorbing and fascinating — the art film at its most accessible. Take a stab at it. —Rod Lott

And you two started complaining about weird things happening, and Dennis set up a couple of totally sweet camcorders ’round the house to see what was what. (Even I gotta admit, rigging the cam on the oscillating fan’s base was ingenious.) And boy, did his DIY spirit pay off! The house had its own invisible demon — Toby, his name was, and he didn’t like to be called fat — who moved objects askew and had this cool trick he liked to do where people would fly across the room like puppets who suddenly had their strings yanked.

And you two started complaining about weird things happening, and Dennis set up a couple of totally sweet camcorders ’round the house to see what was what. (Even I gotta admit, rigging the cam on the oscillating fan’s base was ingenious.) And boy, did his DIY spirit pay off! The house had its own invisible demon — Toby, his name was, and he didn’t like to be called fat — who moved objects askew and had this cool trick he liked to do where people would fly across the room like puppets who suddenly had their strings yanked.

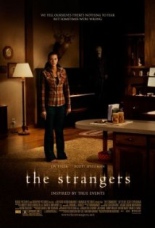

The inconvenience is merely step one of a trio’s ace home-invasion plan. This assault on precinct pretty-boy is made unnerving because the three perpetrators each sport a different mask; according to the credits, their names are Dollface, Pin-up Girl and Man in the Mask. That latter moniker doesn’t do him justice, as he wears a burlap sack with eyeholes and a painted smile. (Pin-up Girl’s facial disguise is particularly creepy; just ask my kids since I was sent one with the review copy. Yes, I am a horrible parent, but I cannot resist a laugh at their piss-their-pants expense.)

The inconvenience is merely step one of a trio’s ace home-invasion plan. This assault on precinct pretty-boy is made unnerving because the three perpetrators each sport a different mask; according to the credits, their names are Dollface, Pin-up Girl and Man in the Mask. That latter moniker doesn’t do him justice, as he wears a burlap sack with eyeholes and a painted smile. (Pin-up Girl’s facial disguise is particularly creepy; just ask my kids since I was sent one with the review copy. Yes, I am a horrible parent, but I cannot resist a laugh at their piss-their-pants expense.)

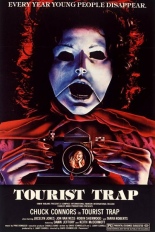

The titular site refers to Slausen’s Lost Oasis, an off-the-beaten path, now-closed-to-the-public wax museum owned by the lonely widowed Mr. Slausen (

The titular site refers to Slausen’s Lost Oasis, an off-the-beaten path, now-closed-to-the-public wax museum owned by the lonely widowed Mr. Slausen (

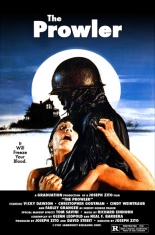

Thirty years later, the town holds the dance again for the first time post-body count, and wouldn’t you know it? The vet is back, and he’s got a hankerin’ to kill all those meddling kids! Perhaps most notably, a busty co-ed gets all points of a pitchfork in her tummy while she’s soaping up in the shower, and Zito doesn’t dare puss out by cutting away.

Thirty years later, the town holds the dance again for the first time post-body count, and wouldn’t you know it? The vet is back, and he’s got a hankerin’ to kill all those meddling kids! Perhaps most notably, a busty co-ed gets all points of a pitchfork in her tummy while she’s soaping up in the shower, and Zito doesn’t dare puss out by cutting away.