Any longtime reader of our sister site, Bookgasm, now 15, knows novelizations run in its blood. I suspect for many of us, movie novelizations were among the first non-children’s novels we read for pleasure. Being born in 1971, I remember a time when such books were the closest one could relive the experience of seeing the film, outside of a re-release or random TV airing. Unlike many of us, however, I kept reading them as an adult, well into this new millennium.

Any longtime reader of our sister site, Bookgasm, now 15, knows novelizations run in its blood. I suspect for many of us, movie novelizations were among the first non-children’s novels we read for pleasure. Being born in 1971, I remember a time when such books were the closest one could relive the experience of seeing the film, outside of a re-release or random TV airing. Unlike many of us, however, I kept reading them as an adult, well into this new millennium.

When I learned of the existence of a new nonfiction book treating the subject of novelizations seriously, instead of scorn, my interest was piqued. As you’ve guessed by now, the title in question is the splendid Light into Ink: A Critical Survey of 50 Film Novelizations, by the UK-based S.M. Guariento.

While doing my due diligence, it was as if a cartoon devil and angel hovered on opposite sides of my head, respectively trying to talk me out of and into buying it:

• “That subtitle sounds so academic, its bones have been drained of marrow.” / “Nonsense, look at those preview pages.”

• “It doesn’t cover the novelizations you’ve expected.” / “So what? Expand those horizons!”

• “It’s self-published!” / “You know that doesn’t mean what it used to. Plus, so were your two favorite books from 2018: Keith Alison’s Cocktails & Capers: Cult Films, Cocktails, Crime and Cool and Howard David Ingham’s We Don’t Go Back: A Watcher’s Guide to Folk Horror.”

• “It costs more than $50.” / “True, but here’s a black-and-white edition for less than $20!”

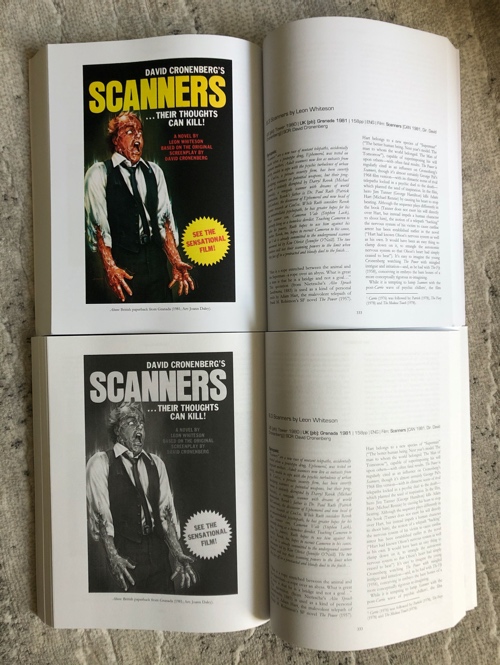

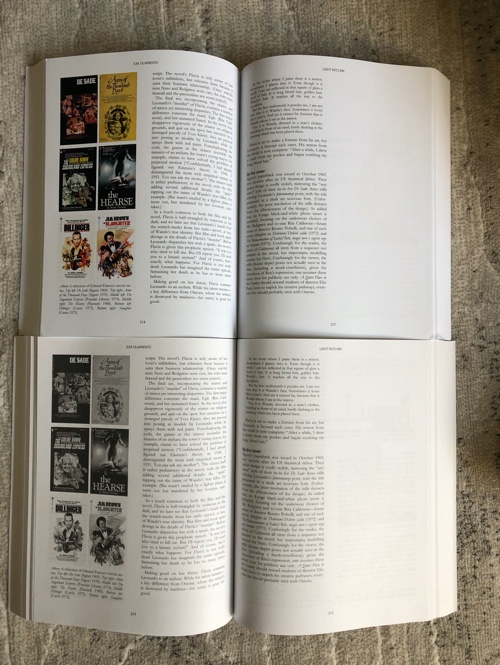

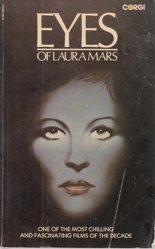

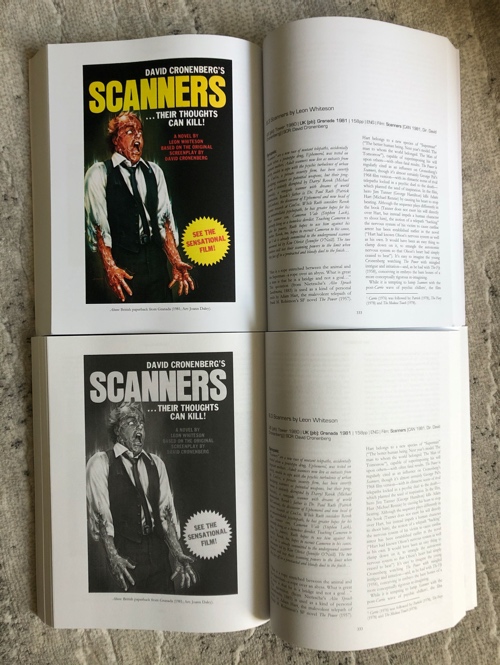

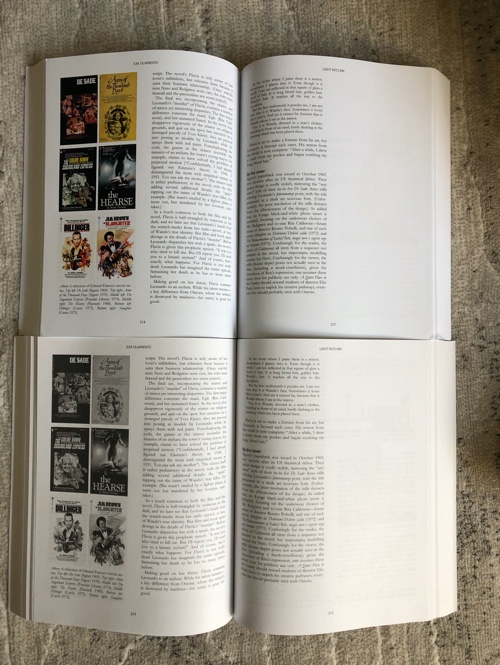

Regarding that last “argument,” Guariento has issued two editions of varying price points: respectively, the splashy, full-color, 480-page DeLuxe edition and the more affordable Midnight edition, whose only differences are being color-free inside and sporting a black cover. Being on the fence, I opted for the more prudent choice of Midnight.

Regarding that last “argument,” Guariento has issued two editions of varying price points: respectively, the splashy, full-color, 480-page DeLuxe edition and the more affordable Midnight edition, whose only differences are being color-free inside and sporting a black cover. Being on the fence, I opted for the more prudent choice of Midnight.

Unfortunately, I loved the book — and I mean absolutely loved it — so naturally I should have kicked myself for not going DeLuxe, right? Instead, I corrected the issue; see the difference for yourself in the sample spreads at the end of this review. Either way, Guariento’s introduction alone is almost worth the purchase price. In just under 50 pages, he gives a thorough, global tour through the history of the novelization, which dates back much further than I assumed: 1608!

What follows amounts to the meat on these bones: full, no-stone-unturned discussions of 50 novelizations, grouped among eight thematic sections that encompass the post-apocalyptic, the satanic, the speculative and even the Italian. The filmographies of John Carpenter and David Cronenberg get their own separate chapters, as do novelizations better than their source material and, finally, novelizations that stand alone as excellent fiction in their own right.

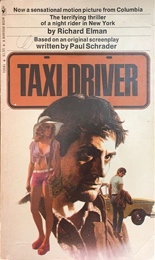

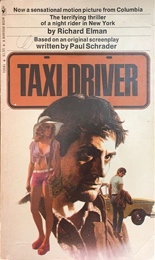

In that last group falls the unlikely Taxi Driver, a literary-minded reimagining of the film’s screenplay, which Richard Elman makes all the more chilling by writing in the first-person POV of perhaps the last character in whose head one would want to spend time: Travis Bickle. Elman’s stream-of-consciousness approach includes clipped verse and thoughts that peter out on the page, bringing out Bickle as an “angry poet in embryo,” as Guariento writes. This chapter, coming toward the book’s end, is the best argument for Light into Ink’s existence.

In that last group falls the unlikely Taxi Driver, a literary-minded reimagining of the film’s screenplay, which Richard Elman makes all the more chilling by writing in the first-person POV of perhaps the last character in whose head one would want to spend time: Travis Bickle. Elman’s stream-of-consciousness approach includes clipped verse and thoughts that peter out on the page, bringing out Bickle as an “angry poet in embryo,” as Guariento writes. This chapter, coming toward the book’s end, is the best argument for Light into Ink’s existence.

Remarkably, not a single chapter fizzles, each adhering to a sturdy framework of context and criticism covering not just the book, but the film itself, the assigned author, the book publisher and its various editions. In essence, Guariento is reviewing as many movies as he is books, but of most value are his comparisons of the two media: what was lost, what was gained and — since authors often had to work from early screenplays that didn’t necessarily represent the final product — what could have been. On one hand, the smash novelization of The Omen, written by the film’s own screenwriter, David Seltzer, is pretty direct, like a bar band covering a hit song with little to no variation; on the other, Dennis Etchison’s translation of Halloween III: Season of the Witch draws upon more of Nigel Kneale’s notoriously discarded screenplay than the sequel that resulted. (Speaking of Kneale, his own Quatermass novel of 1979 earns its own chapter.)

In other words, you’re going to learn a lot. For example, two separate tie-in novels exist for Mad Max 2, The Cat o’ Nine Tails and Capricorn One, all of which are covered here. One of the Capricorn books is penned by Bernard L. Ross, a pseudonym for soon-to-be-famous thriller writer Ken Follett. Guariento covers another title by an author on the cusp of becoming a brand name, Conquest of the Planet of the Apes by none other than John Jakes, as well as an already established bestseller in Christopher Priest‘s eXistenZ, working under a John Luther Novak nom de plume.

In other words, you’re going to learn a lot. For example, two separate tie-in novels exist for Mad Max 2, The Cat o’ Nine Tails and Capricorn One, all of which are covered here. One of the Capricorn books is penned by Bernard L. Ross, a pseudonym for soon-to-be-famous thriller writer Ken Follett. Guariento covers another title by an author on the cusp of becoming a brand name, Conquest of the Planet of the Apes by none other than John Jakes, as well as an already established bestseller in Christopher Priest‘s eXistenZ, working under a John Luther Novak nom de plume.

Those men, however, are the outliers. We won’t count the directors doing their own dirty work (as John Boorman and George A. Romero did as co-authors of the respective Zardoz and Dawn of the Dead tie-ins, both discussed at length herein), but most of Light into Ink’s featured names aren’t recognizable à la Alan Dean Foster, Robert Sheckley or Mike McQuay — and thank God for that, because it allows Guariento to widen his scope to the likes of Hadrian Keene (The Laughing Woman), proving not even Radley Metzger’s porn was immune to riding the tie-in train, no matter how counterintuitive that move may be; and to Phil Smith, whose interpretation of the gory monster mash The Incredible Melting Man is backhandedly celebrated as “pulp trash. … When its aspirations are so deliciously low, can we honestly complain when it achieves them?”

Which brings us to Guariento’s secret weapon: the scalpel. To his credit, he doesn’t dismiss novelizations outright, but when the books are junk, he calls them junk. However vicious his takedowns read — deliciously so — they are equally well-informed, precise and funny. I’m going to share three of my favorite examples:

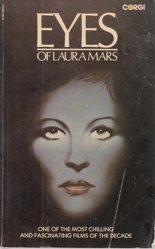

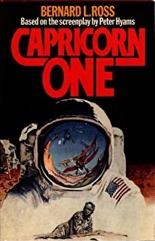

• On Harriet B. Gilmour’s Eyes of Laura Mars: “There’s simply no way to make lines like ‘”Oh no!” she gasped’ read well, for example, and she really ought to have had the good sense to leave ‘Aargh!’, ‘”No!” she screamed’ and, especially, ‘Nooooo…oo…oo!’ in the comic books where she found them.”

• On Harriet B. Gilmour’s Eyes of Laura Mars: “There’s simply no way to make lines like ‘”Oh no!” she gasped’ read well, for example, and she really ought to have had the good sense to leave ‘Aargh!’, ‘”No!” she screamed’ and, especially, ‘Nooooo…oo…oo!’ in the comic books where she found them.”

• On Alan Radnor’s Rabid: “Radnor appears to have left the world of letters in peace, leaving behind him one baffling question: how was he ever allowed inside in the first place? Never was a bush so beaten around by a writer. Faced with a slender script, Radnor seems to have chosen simply to quadruple the word count and hope for the best. … No observation is too trite, no thought too clichéd. Taken together, the effect is cretinising.”

• On Michael Hudson’s The Case of the Bloody Iris: “Never was there a sorrier case of talent outstripped by ego. Hudson is as keen on gore as he is on exclamation marks, but hasn’t the same zeal for proofreading. The text is plagued by missing words, misplaced apostrophes and contagious italics, plus Google Translate gibberish (‘You like the closer, no?’), mangled readymades (‘All of the sudden…’), tautologies (‘Jennifer screamed. They were hysterical screams, and she couldn’t stop’), baffling imagery (‘His face was a large translucent crust’) and gobsmacking illiteracy (‘A gloved hand like what surgeons wore’). Dialogue scenes repeatedly confuse the identity of interlocutors, so that Jennifer ends up interrupting herself, and her ditzy roommate Marilyn somehow discusses her own murder, despite being dead.”

Nothing gets by him, so pity the poor transposed vowel! Whether his prose is irreverent, sober or somewhere in between (“pendulous of bosom and crude of tongue”), I simply love the way Guariento writes across these winning essays. Coupled with several hundred glorious illustrations of cover art, that makes Light into Ink a volume to treasure. —Rod Lott

Get it at Amazon.

While the rest of the country meme-watches its way through the Friends reunion special, the true ’90s nostalgia awaits in the Fantagraphics-published Bleeding Skull! A 1990s Trash-Horror Odyssey.

While the rest of the country meme-watches its way through the Friends reunion special, the true ’90s nostalgia awaits in the Fantagraphics-published Bleeding Skull! A 1990s Trash-Horror Odyssey.  No rave for this book is complete without praise for who may be considered its fourth author: designer Keeli McCarthy. With an aesthetic heavy on Magic Markers, highlighters and the purposeful cut-and-paste sloppiness of zines, her design is more aligned with Carlson’s seminal (and sadly out-of-print) Destroy All Movies!!! The Complete Guide to Punks on Film than Bleeding Skull!’s aforementioned ’80s edition. Either way, it’s now in glorious, garish full color. —Rod Lott

No rave for this book is complete without praise for who may be considered its fourth author: designer Keeli McCarthy. With an aesthetic heavy on Magic Markers, highlighters and the purposeful cut-and-paste sloppiness of zines, her design is more aligned with Carlson’s seminal (and sadly out-of-print) Destroy All Movies!!! The Complete Guide to Punks on Film than Bleeding Skull!’s aforementioned ’80s edition. Either way, it’s now in glorious, garish full color. —Rod Lott