A couple of years ago, the three-part documentary Time Warp: The Greatest Cult Films of All Time hit digital and underwhelmed me by covering all the usual suspects in such short bursts, it offered little new information or insight.

A couple of years ago, the three-part documentary Time Warp: The Greatest Cult Films of All Time hit digital and underwhelmed me by covering all the usual suspects in such short bursts, it offered little new information or insight.

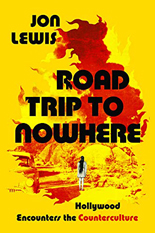

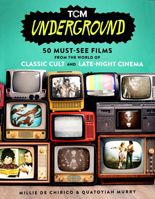

When Turner Classic Movies announced a companion book to TCM Underground, its long-running Friday-night showcase of the similar, I was leery it would be another round of the same well-worn territory. Now that it’s here — TCM Underground: 50 Must-See Films from the World of Classic Cult and Late-Night Cinema — I can happily report I needn’t have worried. Not only do its writers come prepared with plenty of insight, but they include a few movies I’ve never heard of, such 1976’s The Pyramid, a New Age slice of hippie-dippie WTF-ery.

In his foreword, comedian Patton Oswalt (whose movie-minded memoir, Silver Screen Fiend, is a must-read itself) puts readers in the proper mindset by asking them to rethink the requirements for inclusion: “Any movie that punches through the fog of worry, distraction, and ego that we’re stuck in creates a cult, even if it’s a cult of one adherent,” he writes, emphasis mine.

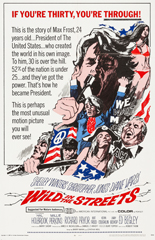

Flicks under discussion are divvied among five categories, from the genres of crime and horror to more nebulous looks at the family unit, rebellion and “mind melters.” The one concession to every other cult-movie list is Russ Meyer’s Beyond the Valley of the Dolls. Beyond that, the heavily illustrated entries — each either four or six colorful pages, all smartly designed by Josh McDonnell — cut a wide swath: Jigoku, Roller Boogie, Satanis: The Devil’s Mass, The Garbage Pail Kids Movie, Shack Out on 101.

Penelope Spheeris’ Decline of Western Civilization docs make up a full 6% of the content. One among the 50 is actually a 10-minute short, Curtis Harrington’s The Wormwood Star. Is that cheating? I’ll allow it. Deep cuts like that go a long way in endearing co-authors Millie De Chirico and Quatoyiah Murry to the reader. So do their compliments like “it all feels like a disjointed, cocaine-fueled splatter of spaghetti thrown against the wall,” which help mitigate the sting of a couple of factual errors — the most egregious stating Brad Pitt’s Once Upon a Time … in Hollywood performance “earned him his first Oscar win.”

Penelope Spheeris’ Decline of Western Civilization docs make up a full 6% of the content. One among the 50 is actually a 10-minute short, Curtis Harrington’s The Wormwood Star. Is that cheating? I’ll allow it. Deep cuts like that go a long way in endearing co-authors Millie De Chirico and Quatoyiah Murry to the reader. So do their compliments like “it all feels like a disjointed, cocaine-fueled splatter of spaghetti thrown against the wall,” which help mitigate the sting of a couple of factual errors — the most egregious stating Brad Pitt’s Once Upon a Time … in Hollywood performance “earned him his first Oscar win.”

Until hosting this trip into Late-Night Cinema, De Chirico and Murry were both new to me. And I’m glad, because I brought no preconceived notions to the book, other than good vibes toward the TCM Underground brand. Now, I feel like I know them well. They share particular affection for Michael Parks, blaxploitation, William Castle and obscurities released (unleashed?) by Something Weird Video and Vinegar Syndrome. They call Mary Woronov and Paul Bartel “the Doris Day and Rock Hudson of B movies.” People who think like that are friends to me, maybe even family. And you’ve gotta support your friends and family. —Rod Lott