To answer your first question: Fervid Filmmaking refers to those movies which author Mike Watt believes to contain everything but the kitchen sink, as if their creators threw in every element imaginable, just in case they never got another chance to direct again.

To answer your first question: Fervid Filmmaking refers to those movies which author Mike Watt believes to contain everything but the kitchen sink, as if their creators threw in every element imaginable, just in case they never got another chance to direct again.

In other words, cinema with “total chaos and total control.” As this paperback’s subtitle promises, he’s chosen exactly 66 of them to spotlight.

To answer your second question: No, he’s not that Mike Watt.

Although I’d be curious to see what cult pics the punk legend recommends, this Mike Watt has written for Film Threat, Fangoria, Femme Fatales and some publications that don’t begin with the letter F. Here, he covers movies I thought only I loved (O.C. and Stiggs), movies I thought only I had seen (Meet the Hollowheads), movies I thought only I had heard of (Sex Machine). That doesn’t mean every film featured is beloved by him (for example, the hippie sketch comedy Dynamite Chicken); it need only fit the criteria. Unsurprisingly, he pretty much loves the majority anyway.

Directors represented include such Hollywood heavyweights as Robert Altman, Steven Soderbergh and George A. Romero, but not for the movies you readily associate with them. On the other side of the spectrum are outré names that include Doris Wishman, William Castle and Lloyd Kaufman (who provides the book’s amusing introduction). And then way, way off said spectrum are names you’ve likely never run across, mostly guys who toil in pixels vs. film.

Directors represented include such Hollywood heavyweights as Robert Altman, Steven Soderbergh and George A. Romero, but not for the movies you readily associate with them. On the other side of the spectrum are outré names that include Doris Wishman, William Castle and Lloyd Kaufman (who provides the book’s amusing introduction). And then way, way off said spectrum are names you’ve likely never run across, mostly guys who toil in pixels vs. film.

But what makes Fervid Filmmaking as throughly enjoyable as it is — only one reason, actually — is that Watt puts them all on a level playing field. Otto Preminger equals Alejandro Jodorowsky equals Alvin Ecarma. Whether their product played to millions of eyeballs in a worldwide theatrical release or has screened to maybe just Watt and his friends via bootleg VHS, no one is placed on an automatic pedestal because of a larger budget. In his view, they’re all filmmakers who took some really ballsy, often unpopular chances, so everyone deserves a salute.

And each essay, arranged alphabetically and sporadically illustrated, is well thought-out, vastly entertaining and even educational. With this book, Watt reveals himself as a legitimate, excellent film critic; this is serious stuff, even if the stuff he discusses deals with a cavewoman clubbing Hitler (Forbidden Zone), a hatred of grapes (Psychos in Love) or David Carradine in drag (Sonny Boy).

And each essay, arranged alphabetically and sporadically illustrated, is well thought-out, vastly entertaining and even educational. With this book, Watt reveals himself as a legitimate, excellent film critic; this is serious stuff, even if the stuff he discusses deals with a cavewoman clubbing Hitler (Forbidden Zone), a hatred of grapes (Psychos in Love) or David Carradine in drag (Sonny Boy).

In-depth without overstaying their welcome, the pieces are all tight, too. The only exception would be Repo! The Genetic Opera, which introduces a cast it then re-introduces a couple pages later. (Outright errors are precious few, too, with the most glaring calling Susan Tyrell an Oscar winner; she didn’t get past the nomination.)

My only other complaint is that Watt’s work is heavy on footnotes. This is fine when he’s imparting supplementary information, but needless when he’s sharing a cast member or creative’s credit, partly because they’re often shared within the main body. For the obsessive like me, they derail the flow of reading, and even more so when the numbers don’t match up, which occurs on several occasions.

No worries, kids; it’s all good. Twenty-five years ago, Fervid Filmmaking would have enjoyed a wide release by one of the major publishing companies, and you would have read a chapter or two at your mall’s Waldenbooks or B. Dalton before realizing this was one that would be worth buying and keeping. In today’s wired world, it has a home with McFarland & Company — a fine publisher, but harder for people to find and priced higher. My hope is that, like the movies Watt shines a light on, the right people will find it, and realize its worth. —Rod Lott

Tim Hensley’s

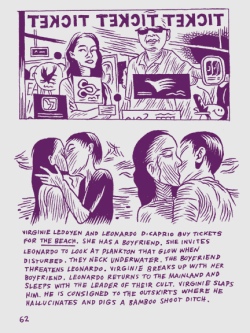

Tim Hensley’s  The scenes Hensley illustrates are not iconic; they appear to be chosen as haphazardly (if “chosen” is the correct term) as the films, which range from highbrow to lowbrow, classic to trash, beloved to obscure,

The scenes Hensley illustrates are not iconic; they appear to be chosen as haphazardly (if “chosen” is the correct term) as the films, which range from highbrow to lowbrow, classic to trash, beloved to obscure,