As completely expected, the films of Ted V. Mikels are much more fun to read about than they are to watch. Unlike a chosen few directors, let’s just say the guy had his work end up featured on an episode of Mystery Science Theater 3000 for damned good reason.

As completely expected, the films of Ted V. Mikels are much more fun to read about than they are to watch. Unlike a chosen few directors, let’s just say the guy had his work end up featured on an episode of Mystery Science Theater 3000 for damned good reason.

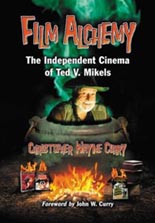

Christopher Wayne Curry, author of Film Alchemy: The Independent Cinema of Ted V. Mikels, doesn’t quite see it that way; he worships the works, but he also considers Mikels a friend and heaps “love, respect and admiration” on the filmmaker. Also in his introduction, Curry calls Mikels the single most interesting figure in exploitation cinema, deserving of mention alongside Russ Meyer. I realize such things are subjective, but he’s obviously approached the book with a blinded bias. It’s enough to make you want to cry, “Get a room!”

That is its biggest downfall, but guess what? I still recommend it, because even with the absence of impartiality, the book remains a blast to read.

A much more affordable paperback reprint of McFarland original 2008 hardback release, the slim Film Alchemy takes readers on a detailed, chronological journey through Mikels’ complete CV as director (well, complete as of 2008), starting with the 1963 thriller Strike Me Deadly to the 2006 family drama (!) Heart of a Boy. Most cult cinephiles, however, know Mikels best for a few that land in between — namely, 1968’s The Astro-Zombies (to which he’s still cranking out unwanted sequels), 1971’s The Corpse Grinders and 1973’s The Doll Squad (ripped off by Aaron Spelling for the TV series Charlie’s Angels, if Ted is to be believed).

Ted’s quite a character (polygamists tend to be) and he has great stories to share about the making of these no-budget epics. But his story prowess does not extend to the screen; Ed Wood looks masterful by comparison. The four flicks of his I’ve seen have all been really tough sits, and Lord knows I’m more forgiving than most when it comes to B and Z cinema.

Yet Mikels seems unaware of all his limitations, to the point of delusion, and Curry is right along with him. Only when the book approaches the VHS age of Mikels’ career does Curry cede to admitting shortcomings. And as the movies get less interesting, so does the book; after all, Mission: Killfast, although a terrific title, has yet to resonate with any degree of pop-culture impact and likely never will.

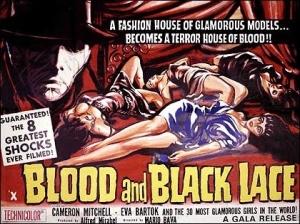

Film Alchemy is highly recommend to Mikels’ fan base and just plain recommended to those with a love of bad movies. The book pops with a wealth of photos and poster art. One can see how easy it would have been at the time to get suckered in by such much-to-promise visuals. —Rod Lott