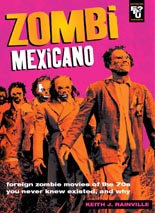

Fans of outré horror cinema are urged to order Zombi Mexicano right freakin’ now — not just because it’s an excellent publication, but because author/designer Keith J. Rainville has printed only 250 of these babies, with no plans for a wider run.

Fans of outré horror cinema are urged to order Zombi Mexicano right freakin’ now — not just because it’s an excellent publication, but because author/designer Keith J. Rainville has printed only 250 of these babies, with no plans for a wider run.

In other words: You snooze, you lose, and the trade paperback represents 20 of my dollars that were as hard-earned as they were well-spent.

¿Comprende?

Zombi Mexicano is not a definitive text on Mexican zombie flicks, nor is it intended to be (although now I’m convinced he should embark on that project immediately). It is an overview on a franchise that Rainville believes has been ignored, and he’s right; even a cult-film enthusiast such as myself hadn’t heard of the “Guanajuato mummies” movies, not to mention their producer, Rogelio Agrasánchez Linaje.

As Rainville writes, “Ever see a zombie use karate, then try to stomp a baby, all to the tune of a circus pipe organ?” I can’t say that I have, but I can say that I must.

As Rainville writes, “Ever see a zombie use karate, then try to stomp a baby, all to the tune of a circus pipe organ?” I can’t say that I have, but I can say that I must.

Numbering roughly seven or so films, the series began with 1970’s The Mummies of Guanajuato, starring the “holy trinity of lucha-heroes: Santo, Blue Demon and Mil Mascaras.” Following in quick succession over the next five years were such sequels as Castle of the Mummies of Guanajuato, Mansion of the Seven Mummies and Macabre Legends of the Colonial Era.

I now need to see all of them.

Rainville runs through each with a spirited discussion that’s supplemented with scads and scads of crazy screen grabs, vintage posters and garish lobby cards. It’s laid out like a magazine, professionally and in eye-popping full color (except those instances where the source material was not).

The jam-packed 64-pager also contains an introductory essay that touches upon the movies you likely have heard of (i.e. the Aztec Mummy trilogy) and Mexico’s yesteryear comics featuring zombies and/or mummies.

So you don’t just have to take my near-worthless word for it, you can get a peek at Zombi Mexicano‘s insides here. Now go buy it, funky film fan, before that right is taken from you. I accept your thanks in advance. De nada. —Rod Lott