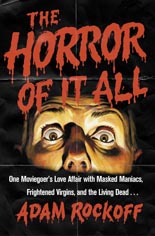

Thus far, 2015 has brought us two movie-loving memoirs from major publishers: Comedian Patton Oswalt’s Silver Screen Fiend ushered in the New Year and now Adam Rockoff greets the sweltering months with The Horror of It All. Rockoff is just the guy you don’t know by name.

Thus far, 2015 has brought us two movie-loving memoirs from major publishers: Comedian Patton Oswalt’s Silver Screen Fiend ushered in the New Year and now Adam Rockoff greets the sweltering months with The Horror of It All. Rockoff is just the guy you don’t know by name.

Or at least comparatively speaking. Fright fans — the crowd most likely to snap up this heartfelt hardback — may know Rockoff as the author of 2002’s Going to Pieces: The Rise and Fall of the Slasher Film (a nifty book which became the nifty documentary of the same name) and as the screenwriter of 2010’s I Spit on Your Grave remake. Okay, so he actually hid behind a pseudonym on that project, and the reason why makes for one of many good stories in The Horror of It All.

Unlike Oswalt’s book, which carries a narrative through-line, Rockoff’s could qualify as an essay collection. Although its breath-robbing subtitle (One Moviegoer’s Love Affair with Masked Maniacs, Frightened Virgins, and the Living Dead … ) suggests an adherence to fiction’s three-act structure, that tale is more or less told in the first chapter. It and the other nine aren’t really linked, other than that they are:

a) full of the author’s opinions, and

b) about horror movies.

Each can stand alone. And there’s absolutely nothing wrong with that. Not when they’re this damned entertaining.

In chapter two, Rockoff rips apart the now-notorious 1980 episode of Sneak Previews, in which Gene Siskel and Roger Ebert hypocritically decried the trend of slasher movies, while chapter seven examines supposed “snuff” films, from (what else?) Snuff and Faces of Death to Guinea Pig and, ergo, the extreme gullibility of Charlie Sheen.

Others pieces are historical-minded. One details the PMRC Senate hearings/attacks on heavy metal music; another, how the 1996 release of Wes Craven’s Scream resurrected the moribund genre of horror for the big screen to a degree that it has yet to abate (and, he argues with extreme confidence, never will).

And other sections are more personal, such as chapter four, dedicated to how and why the author’s teenaged self turned down a hand job in favor of watching a VHS tape full of horror trailers. He peppers the book with such nostalgic asides, from seeing his first Playboy to trolling the local flea market for life-altering issues of Fangoria.

Of that bargain-bonanza site, he writes, “Where else could you possibly find Chinese stars, a rattlesnake paperweight, and a ‘Kill a Commie for Mommy’ T-shirt within fifty yards of each other?” I bring this quote up to illustrate Rockoff’s most welcome sense of humor, which permeates every page; of renting vids with his buddies way back when: “And we had our minds blown by Sleepaway Camp. Sure, the film’s gender politics might have escaped us, but sometimes a girl with a dick trumps all.”

As if you couldn’t tell, Rockoff is unafraid to say what’s on his mind, even when it comes to admittedly (and wildly) unpopular opinions, such as Ridley Scott’s classic Alien being boring, Brett Ratner’s Red Dragon reigning superior over Michael Mann’s Manhunter, and — sacrilege of sacrileges! — the iconic shower scene of Alfred Hitchcock’s Psycho being “totally overrated … one big letdown.” (Don’t shoot the messenger, folks.)

If there’s an element to dislike about The Horror of It All, it’s not his mass slaughtering of sacred cows; after all, he presents them with conviction and compelling arguments. It’s that in the back half of the book, he increasingly comes off as kind of an asshole, as even the most well-constructed defense tends to come undone when it concludes with “Fuck you” or a variation thereof. At least these instances are few, none of which — alone or collectively — detract from the sheer enjoyment of reading the book, which I did in one weekend afternoon and instead of watching a horror movie. That’s how much fun it is. —Rod Lott

Get it at Amazon.

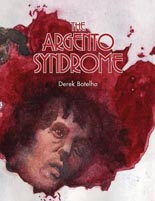

As a fan of Dario Argento myself, I feel as if Derek Botelho wrote The Argento Syndrome just for me. Although Maitland McDonagh’s Broken Mirrors/Broken Minds is arguably the definitive book on the director famously dubbed (and derided) as “the Italian Hitchcock,” Botelho’s has the edge for pure entertainment value. Both books are musts for the filmmaker’s followers, as each takes a different tact.

As a fan of Dario Argento myself, I feel as if Derek Botelho wrote The Argento Syndrome just for me. Although Maitland McDonagh’s Broken Mirrors/Broken Minds is arguably the definitive book on the director famously dubbed (and derided) as “the Italian Hitchcock,” Botelho’s has the edge for pure entertainment value. Both books are musts for the filmmaker’s followers, as each takes a different tact.

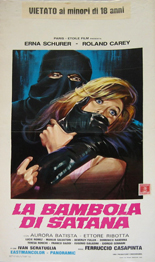

Naturally, the more iconic and influential the film, the more Curti has to say about it; for example, I think nothing eclipses Mario Bava’s

Naturally, the more iconic and influential the film, the more Curti has to say about it; for example, I think nothing eclipses Mario Bava’s