Fervent fans of their subject, Louis R. Pisano and Michael A. Smith have joined forces to tell the story of Jaws 2: The Making of the Hollywood Sequel, published in both hardcover and paperback by BearManor Media. To be brutally honest, the tale was told much better in another BearManor release, 2009’s Just When You Thought It Was Safe: A Jaws Companion, in which author Patrick Jankiewicz covers Universal’s entire shark-flick franchise.

Fervent fans of their subject, Louis R. Pisano and Michael A. Smith have joined forces to tell the story of Jaws 2: The Making of the Hollywood Sequel, published in both hardcover and paperback by BearManor Media. To be brutally honest, the tale was told much better in another BearManor release, 2009’s Just When You Thought It Was Safe: A Jaws Companion, in which author Patrick Jankiewicz covers Universal’s entire shark-flick franchise.

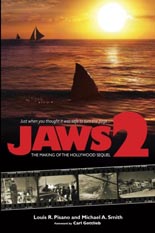

To Pisano and Smith’s collective credit, they have interviewed damn near everyone still alive who was involved with the inferior (yet still beloved and highly profitable) sequel. Their passion for the finished product shows. They have uncovered a wealth of storyboards and photos from the set to satisfy the most ardent of Jaws 2 admirers. They even wrangled Carl Gottlieb, co-screenwriter of the first three films, to provide the foreword.

If only their work had gone through a judicious edit, as the book is filled with inconsistencies, repeated information and unprofessional passages.

The sloppiness is subtle at first, as a mention of Steven Spielberg’s Close Encounters of the Third Kind morphs into 3rd Kind just three paragraphs later. Little things like that start popping up with greater frequency, like spawn of the Surinam toad. If it’s not awkward phrasing (“of the filming of the original film”), it may be a run-on sentence that could have been saved with a single comma: “Prior to heading to Martha’s Vineyard to shoot the cast spent countless hours every day learning to sail under the watchful eyes of Ellen Demmy.”

Instances of the authors’ “narration” (I don’t know what else to call it) struck me as especially bizarre, as they stop to address the reader in a manner that half-assumes said reader doesn’t understand how a book works, such as the concept of progressing from one chapter to the next. For example: “You will learn much more about the Florida shoot, throughout the stories of the cast and crew, later on in the book. To mention certain things here would only spoil your upcoming reading. No one likes to know what happens before they read a book or watch a movie. Read on and we promise, you won’t be disappointed.”

And yet, I was, greatly. The major behind-the-scenes events of Jaws 2’s troubled production were covered really well in Jankiewicz’s earlier text, particularly the story ideas that never came to be, the dismissal of original director John Hancock (Let’s Scare Jessica to Death), Roy Scheider’s disgust for reprising his starring role of Chief Brody, and Scheider’s fisticuffs with replacement director Jeannot Szwarc (1984’s Supergirl).

Even if I had not read the Jankiewicz book, however, I still would have to take issue with the way such stories are presented by Pisano and Smith, which is to say “twice.” So many anecdotes are repeated in full. Take, for instance, their recounting of producers Dick Zanuck and David Brown recruiting Howard Sackler for screenplay duties. First, from page 2 (with their errors intact):

“Not dissuaded, the producers contacted Howard Sackler. Sackler, a playwright whose works include The Great White Hope, winner of both the Pulitzer Prize and the Tony Award for Best Play. A friend of Browns’, as a favor Sackler had done a re-write on Benchley’s original script for Jaws and was familiar with the material. It was Sackler who suggested that the character of Quint’s hatred toward sharks stemmed from his being a survivor of the attack on, and sinking of, the U.S.S. Indianapolis towards the end of World War II. The scene where Quint recalls the event, later re-written, in part, by Gottlieb and actor Robert Shaw, remains one of the most memorable in film history. Keen on the idea, Sackler met with Zanuck and Brown and suggested, not a sequel but a prequel. What if the film detailed the mission of the U.S.S. Indianapolis …”

Now, four chapters later, from page 53:

“Before 1975, if you knew the name Howard Sackler it was because he was the author behind the 1969 Broadway play The Great White Hope, which won Sackler the Tony and New York Drama Critics Circle award as the year’s Best Play as well as the Pulitzer Prize for Drama. A friend of film producer David Brown, Sackler accepted the offer to do a re-write on Jaws author Peter Benchley’s script for the film version of his novel. Sackler’s main contribution to the story was the back story that the shark fisherman, Quint, derived his hatred for sharks from having survived the sinking of the U.S.S. Indianapolis in July of 1945. … When Brown and his producing partner, Richard Zanuck, approached Sackler about writing Jaws 2, Sackler’s first idea was to write about the Indianapolis incident.”

Similar duplication occurs with stories of other Jaws 2 contributors: Gottlieb on pages 3 and 55; Lorraine Gary and Murray Hamilton, pages 4 and 9; Jeffrey Kramer, pages 4 and 11. I stopped keeping track, but their regurgitation is inexcusable.

The authors’ coup, as it were, is in interviewing so many of the “Amity Kids,” from both the Hancock and Szwarc regimes about their recollections. Much overlap exists here, too, yet that’s somewhat expected since they’re all talking about the same topic. Still, their answers appear to have printed verbatim, and could have been trimmed for better flow. —Rod Lott

Get it at Amazon or BearManor Media.