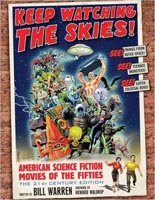

Maybe it’s just me, but the title of Bill Warren’s Keep Watching the Skies! may serve as a warning, i.e., you could get so wrapped up as to lose all sense of time. That’s certainly not a stretch, although arm strain could cut your reading session short. Subtitled American Science Fiction Movies of the Fifties, the book is such a behemoth that McFarland & Company has split it into two volumes (not sold separately) whose 1,000-plus pages collectively weigh nearly 6 pounds! First published in 1982, Keep Watching has been revised cover to cover (to cover to cover) for this 21st Century Edition, as Warren has revisited every film featured — now arranged alphabetically, from Abbott and Costello Go to Mars to X the Unknown — as well as added new entries. To call this massive undertaking a life’s work is not hyperbole. If each movie were represented by a mere pithy capsule review, a thumbs-up would not be automatic; instead, Warren affords each with a full, thought-out essay. Illustrations abound, with color pages of original posters inserted in the center of both volumes, kicking this project into that rarest of recommendations: unequivocally essential for the bookshelf of every cult-film fanatic.

Maybe it’s just me, but the title of Bill Warren’s Keep Watching the Skies! may serve as a warning, i.e., you could get so wrapped up as to lose all sense of time. That’s certainly not a stretch, although arm strain could cut your reading session short. Subtitled American Science Fiction Movies of the Fifties, the book is such a behemoth that McFarland & Company has split it into two volumes (not sold separately) whose 1,000-plus pages collectively weigh nearly 6 pounds! First published in 1982, Keep Watching has been revised cover to cover (to cover to cover) for this 21st Century Edition, as Warren has revisited every film featured — now arranged alphabetically, from Abbott and Costello Go to Mars to X the Unknown — as well as added new entries. To call this massive undertaking a life’s work is not hyperbole. If each movie were represented by a mere pithy capsule review, a thumbs-up would not be automatic; instead, Warren affords each with a full, thought-out essay. Illustrations abound, with color pages of original posters inserted in the center of both volumes, kicking this project into that rarest of recommendations: unequivocally essential for the bookshelf of every cult-film fanatic.

Fresh from counting down the subjective 100 Greatest Science-Fiction Films, author Douglas Brode returns — this time with tongue a-waggin’ — to ogle luscious ladies in Deadlier than the Male: Femme Fatales in 1960s and 1970s Cinema. For the BearManor Media trade paperback, Brode profiles more than 100 of not necessarily the silver screen’s most golden goddesses, but those who also played it rough as villainesses. Thus, we get a lot of Bond girls and Hammer vixens, but dozens more hailing from the seamier side of exploitation cinema. Each woman is introduced with quick vital stats, such as her measurements (when available), before Brode digs in for a big-picture overview of her life and career, often with appropriately tongue-in-cheek self-awareness. For example, of Barbara Steele, he writes that “mostly her work consisted of being bound and gagged in old castles.” This goes a long way in mitigating Brode’s crime of misspelling names: Dianne Thorne, Silvia Kristel and Carol Baker, to point out just three errors. Among 522 jam-packed pages, rarely a spread goes by without a photo, almost all of which are dead-sexy. And, like the actresses’ films, several shots contain nudity, so keep away from prying eyes! I read this front to back over the course of several weeknights; if I were 14, it would be embarrassingly dog-eared … and not so much from “reading,” per se. 😉

Fresh from counting down the subjective 100 Greatest Science-Fiction Films, author Douglas Brode returns — this time with tongue a-waggin’ — to ogle luscious ladies in Deadlier than the Male: Femme Fatales in 1960s and 1970s Cinema. For the BearManor Media trade paperback, Brode profiles more than 100 of not necessarily the silver screen’s most golden goddesses, but those who also played it rough as villainesses. Thus, we get a lot of Bond girls and Hammer vixens, but dozens more hailing from the seamier side of exploitation cinema. Each woman is introduced with quick vital stats, such as her measurements (when available), before Brode digs in for a big-picture overview of her life and career, often with appropriately tongue-in-cheek self-awareness. For example, of Barbara Steele, he writes that “mostly her work consisted of being bound and gagged in old castles.” This goes a long way in mitigating Brode’s crime of misspelling names: Dianne Thorne, Silvia Kristel and Carol Baker, to point out just three errors. Among 522 jam-packed pages, rarely a spread goes by without a photo, almost all of which are dead-sexy. And, like the actresses’ films, several shots contain nudity, so keep away from prying eyes! I read this front to back over the course of several weeknights; if I were 14, it would be embarrassingly dog-eared … and not so much from “reading,” per se. 😉

Don’t let the highfalutin word in the subtitle keep you from Cycles, Sequels, Spin-offs, Remakes, and Reboots: Multiplicities in Film and Television. Edited by Amanda Ann Klein and R. Barton Palmer, this is a highly accessible look at why a franchise-crazed Hollywood is so fond of using and reusing the same concepts and stories. (The short answer: Because audiences pay in droves to see them.) From Dumbledore to mumblecore, this wonderful collection of 17 essays brims with sharp insights; for instance, the practice of capitalizing on familiarity dates back to cinema’s infancy, as Thomas Edison released a film based upon a popular novelty postcard in 1905. Standouts in this University of Texas Press trade paperback include Chelsea Crawford’s piece on American remakes of J-horror hits; Constantine Verevis’ use of the Jaws series to illustrate the When Animals Attack-style trend of the 70s (although calling Steven Spielberg’s undisputed classic a “disaster film” is terminology I take umbrage with); Robert Rushing considers how the waves of peplum, from Steve Reeves’ Hercules to the more recent Brett Ratner and Renny Harlin versions, play with sexuality; and Kathleen Loock’s examination of the major studios’ current fascination with reviving properties of the 1980s. However, another Kathleen — Williams — provides the most interesting chapter, on the YouTube phenomenon of retooled trailers, both by fans and, in the unique case of Snakes on a Plane, by execs.

Don’t let the highfalutin word in the subtitle keep you from Cycles, Sequels, Spin-offs, Remakes, and Reboots: Multiplicities in Film and Television. Edited by Amanda Ann Klein and R. Barton Palmer, this is a highly accessible look at why a franchise-crazed Hollywood is so fond of using and reusing the same concepts and stories. (The short answer: Because audiences pay in droves to see them.) From Dumbledore to mumblecore, this wonderful collection of 17 essays brims with sharp insights; for instance, the practice of capitalizing on familiarity dates back to cinema’s infancy, as Thomas Edison released a film based upon a popular novelty postcard in 1905. Standouts in this University of Texas Press trade paperback include Chelsea Crawford’s piece on American remakes of J-horror hits; Constantine Verevis’ use of the Jaws series to illustrate the When Animals Attack-style trend of the 70s (although calling Steven Spielberg’s undisputed classic a “disaster film” is terminology I take umbrage with); Robert Rushing considers how the waves of peplum, from Steve Reeves’ Hercules to the more recent Brett Ratner and Renny Harlin versions, play with sexuality; and Kathleen Loock’s examination of the major studios’ current fascination with reviving properties of the 1980s. However, another Kathleen — Williams — provides the most interesting chapter, on the YouTube phenomenon of retooled trailers, both by fans and, in the unique case of Snakes on a Plane, by execs.

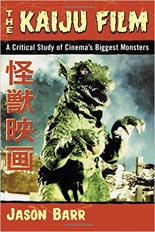

Godzilla, Gamera and all their oversized, radiated ilk: Are they worthy of the intense critical examination afforded to “important” foreign films? Jason Barr sure as hell thinks so, and The Kaiju Film: A Critical Study of Cinema’s Biggest Monsters sure as hell serves as proof. Published in trade paperback by McFarland, this may be the most sober book ever written and that ever will be written on the subject, as Barr takes these films very seriously. Irked at pop culture’s broad view of these movies as greasy kids’ stuff, he takes a slight dig at William Tsutsui’s Godzilla on My Mind for being “flippant” in tone, yet at least that 2004 book was a delight to read. Barr clearly has won the war of expertise, because chapter by chapter, he illustrates an incredible depth of knowledge not just in the aforementioned franchises, but as the giant-monster genre as a whole is informed by Asian traditions predating cinema and interested in making pointed political statements (not all of which lurk as subtext — Godzilla vs. the Smog Monster, anyone?). The Kaiju Film is intelligent, all right. I just wish it also were fun. It’s essentially a thesis, not a reference work; take that into account as you decide responsibly. —Rod Lott

Godzilla, Gamera and all their oversized, radiated ilk: Are they worthy of the intense critical examination afforded to “important” foreign films? Jason Barr sure as hell thinks so, and The Kaiju Film: A Critical Study of Cinema’s Biggest Monsters sure as hell serves as proof. Published in trade paperback by McFarland, this may be the most sober book ever written and that ever will be written on the subject, as Barr takes these films very seriously. Irked at pop culture’s broad view of these movies as greasy kids’ stuff, he takes a slight dig at William Tsutsui’s Godzilla on My Mind for being “flippant” in tone, yet at least that 2004 book was a delight to read. Barr clearly has won the war of expertise, because chapter by chapter, he illustrates an incredible depth of knowledge not just in the aforementioned franchises, but as the giant-monster genre as a whole is informed by Asian traditions predating cinema and interested in making pointed political statements (not all of which lurk as subtext — Godzilla vs. the Smog Monster, anyone?). The Kaiju Film is intelligent, all right. I just wish it also were fun. It’s essentially a thesis, not a reference work; take that into account as you decide responsibly. —Rod Lott