One-night-only engagements and George Lucas tinkering notwithstanding, nowadays it pretty much takes the death of a beloved celebrity to get old movies back on the big screens of the multiplex; witness the recent passing of Prince and Gene Wilder, and the immediate return of Purple Rain and Young Frankenstein to first-run theaters. Once upon a time, however — the days before cable TV and VHS, to be exact — reissues were likely the only way audiences would get another chance to see a particular motion picture. Brian Hannan examines this bygone phenomenon in Coming Back to a Theater Near You: A History of Hollywood Reissues, 1914-2014, published in trade paperback by McFarland & Company. In admittedly “forensic detail,” Hannan chronologically examines this business model of sloppy seconds — initially a financial necessity for studios yet despised by exhibitors (until television and James Bond double-bills changed their tune). While the author grants big-picture visibility throughout this unusual slice of Hollywood history, his case studies — using films as disparate as Gone with the Wind and Reefer Madness — offer the greatest entertainment value. So thorough is Hannan, the footnotes to chapter one alone number 470! Don’t think that dedication to research translates into a wan read; Coming Back is a lively look back, packed with scads of incredible ads and posters that illustrate a peculiar sort of Tinseltown ballyhoo.

One-night-only engagements and George Lucas tinkering notwithstanding, nowadays it pretty much takes the death of a beloved celebrity to get old movies back on the big screens of the multiplex; witness the recent passing of Prince and Gene Wilder, and the immediate return of Purple Rain and Young Frankenstein to first-run theaters. Once upon a time, however — the days before cable TV and VHS, to be exact — reissues were likely the only way audiences would get another chance to see a particular motion picture. Brian Hannan examines this bygone phenomenon in Coming Back to a Theater Near You: A History of Hollywood Reissues, 1914-2014, published in trade paperback by McFarland & Company. In admittedly “forensic detail,” Hannan chronologically examines this business model of sloppy seconds — initially a financial necessity for studios yet despised by exhibitors (until television and James Bond double-bills changed their tune). While the author grants big-picture visibility throughout this unusual slice of Hollywood history, his case studies — using films as disparate as Gone with the Wind and Reefer Madness — offer the greatest entertainment value. So thorough is Hannan, the footnotes to chapter one alone number 470! Don’t think that dedication to research translates into a wan read; Coming Back is a lively look back, packed with scads of incredible ads and posters that illustrate a peculiar sort of Tinseltown ballyhoo.

Man, what can’t Neil Gaiman write? (“Poorly” may be the answer, although the question was rhetorical.) Although famous for his fiction across novels both prose (American Gods) and graphic (The Sandman), the fantastic fantasist got his start in nonfiction. Published by William Morrow, The View from the Cheap Seats: Selected Nonfiction is not a collection of that early journalism, but nearly 100 essays he has penned — plus reviews he has written, speeches he has given, introductions he has contributed — since “making it.” The title refers to his surreal experience at the Oscars in 2010; attending for Coraline, an excellent animated adaptation of his 2002 YA work, the out-of-element author recounts crossing paths with Steve Carell, Michael Sheen and the Westboro Baptist Church. The movies constitute an admirable chunk of Cheap Seats’ contents, with an appreciation of The Bride of Frankenstein; three pieces on pal Dave McKean’s MirrorMask, for which he wrote the screenplay (with Gaiman’s Sundance diary being the best of the trio and somewhat of a companion to the title article); and, for the small screen, childhood nostalgia for Doctor Who. You’ll also find pages on music, comics and a lot of lit — all splendidly crafted, no matter the topic.

Man, what can’t Neil Gaiman write? (“Poorly” may be the answer, although the question was rhetorical.) Although famous for his fiction across novels both prose (American Gods) and graphic (The Sandman), the fantastic fantasist got his start in nonfiction. Published by William Morrow, The View from the Cheap Seats: Selected Nonfiction is not a collection of that early journalism, but nearly 100 essays he has penned — plus reviews he has written, speeches he has given, introductions he has contributed — since “making it.” The title refers to his surreal experience at the Oscars in 2010; attending for Coraline, an excellent animated adaptation of his 2002 YA work, the out-of-element author recounts crossing paths with Steve Carell, Michael Sheen and the Westboro Baptist Church. The movies constitute an admirable chunk of Cheap Seats’ contents, with an appreciation of The Bride of Frankenstein; three pieces on pal Dave McKean’s MirrorMask, for which he wrote the screenplay (with Gaiman’s Sundance diary being the best of the trio and somewhat of a companion to the title article); and, for the small screen, childhood nostalgia for Doctor Who. You’ll also find pages on music, comics and a lot of lit — all splendidly crafted, no matter the topic.

And now for something that could start as many arguments as the current presidential election: TV (The Book): Two Experts Pick the Greatest American Shows of All Time. Undertaking this rather intimidating endeavor with due diligence, noted boob-tube critics Matt Zoller Seitz and Alan Sepinwall have ranked and reviewed the finest 100 U.S. series in the history’s medium. After a maddeningly redundant introductory chapter that preserves their Google Chat debate on whether The Simpsons or The Sopranos is most deserving to claim that No. 1 slot (spoiler: Homer > Tony), the paperback functions as the kind of dynamic reference work that movies get all the time, while television rarely does. In our era of binge-watching and “peak TV,” their book is perfectly timed (if already dated) and rife with thoughtful, helpful, why-it-matters essays on such picks as Cheers, Twin Peaks, Batman, St. Elsewhere and Police Squad! Their taste is near-impeccable — How I Met Your Mother?!? — and extends beyond the top 100 to shout-out current newbies likely to land on the list in future editions, shows of “a certain regard” that didn’t quite make the cut (from the short-lived Kolchak: The Night Stalker to season one of True Detective) and top-10 lists of made-for-TV movies, miniseries and live plays. Peppered throughout are looser lists to celebrate the finest in theme songs, pilots, finales, bosses, homes, ridiculous names and memorable deaths (Chuckles, we hardly knew ye). Despite the dead-serious approach (not to mention insane algorithms) Seitz and Sepinwall take to their self-imposed assignment, fun is first and foremost the name of their game. It earns the equivalent of the TiVo Season Pass.

And now for something that could start as many arguments as the current presidential election: TV (The Book): Two Experts Pick the Greatest American Shows of All Time. Undertaking this rather intimidating endeavor with due diligence, noted boob-tube critics Matt Zoller Seitz and Alan Sepinwall have ranked and reviewed the finest 100 U.S. series in the history’s medium. After a maddeningly redundant introductory chapter that preserves their Google Chat debate on whether The Simpsons or The Sopranos is most deserving to claim that No. 1 slot (spoiler: Homer > Tony), the paperback functions as the kind of dynamic reference work that movies get all the time, while television rarely does. In our era of binge-watching and “peak TV,” their book is perfectly timed (if already dated) and rife with thoughtful, helpful, why-it-matters essays on such picks as Cheers, Twin Peaks, Batman, St. Elsewhere and Police Squad! Their taste is near-impeccable — How I Met Your Mother?!? — and extends beyond the top 100 to shout-out current newbies likely to land on the list in future editions, shows of “a certain regard” that didn’t quite make the cut (from the short-lived Kolchak: The Night Stalker to season one of True Detective) and top-10 lists of made-for-TV movies, miniseries and live plays. Peppered throughout are looser lists to celebrate the finest in theme songs, pilots, finales, bosses, homes, ridiculous names and memorable deaths (Chuckles, we hardly knew ye). Despite the dead-serious approach (not to mention insane algorithms) Seitz and Sepinwall take to their self-imposed assignment, fun is first and foremost the name of their game. It earns the equivalent of the TiVo Season Pass.

It only took several hundred years, but that anti-Santa demon known as the Krampus finally has become an American celebrity, thanks to movies like A Christmas Horror Story, Night of the Krampus, Krampus: The Reckoning, Krampus: The Christmas Devil and just plain ol’ Krampus. Exactly from where did this unconventional leading man come? That’s the global-spanning goal — cleared! — of performance artist Al Ridenour in The Krampus and the Old, Dark Christmas: Roots and Rebirth of the Folkloric Devil. Using the baby-consuming creature’s recent cinematic surge as a launching pad, Ridenour explores the horrific goat-man’s European origins, town-to-town traditions (Buttnmandl, anyone?), stage appearances and more, all pithy and neatly arranged under subheads for easy-to-digest reading. Personally, I would have preferred more focus on the aspect of pure pop culture. One of the most appealing chapters introduces readers to the Krampus’ monstrous relatives, such as Pinecone Man. As is the modus operandi of outré publisher Feral House (whose recent volumes on Grand Guignol theater, sleazy sex novels of the 1960s and men’s adventure pulp magazines are all incredible), this trade paperback is a veritable visual feast of maps, photos and possbily insane vintage illustrations. So visual is The Krampus that it’s quite possible that functionally illiterate could spend time leafing through its pages and emerge satisfied, but why? They’d miss out on half the fun. —Rod Lott

It only took several hundred years, but that anti-Santa demon known as the Krampus finally has become an American celebrity, thanks to movies like A Christmas Horror Story, Night of the Krampus, Krampus: The Reckoning, Krampus: The Christmas Devil and just plain ol’ Krampus. Exactly from where did this unconventional leading man come? That’s the global-spanning goal — cleared! — of performance artist Al Ridenour in The Krampus and the Old, Dark Christmas: Roots and Rebirth of the Folkloric Devil. Using the baby-consuming creature’s recent cinematic surge as a launching pad, Ridenour explores the horrific goat-man’s European origins, town-to-town traditions (Buttnmandl, anyone?), stage appearances and more, all pithy and neatly arranged under subheads for easy-to-digest reading. Personally, I would have preferred more focus on the aspect of pure pop culture. One of the most appealing chapters introduces readers to the Krampus’ monstrous relatives, such as Pinecone Man. As is the modus operandi of outré publisher Feral House (whose recent volumes on Grand Guignol theater, sleazy sex novels of the 1960s and men’s adventure pulp magazines are all incredible), this trade paperback is a veritable visual feast of maps, photos and possbily insane vintage illustrations. So visual is The Krampus that it’s quite possible that functionally illiterate could spend time leafing through its pages and emerge satisfied, but why? They’d miss out on half the fun. —Rod Lott

Get them at Amazon.

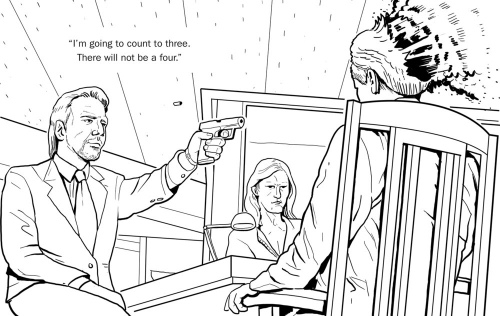

Methinks this coloring-book craze for adults has gotten way out of hand, and it was questionable to begin with. Now we have Die Hard: The Authorized Coloring and Activity Book welcoming itself to the party, pal, and it is at once a coattails-riding cash grab for 20th Century Fox and a knowing parody of the fad by stand-up comedian Doogie Horner, who wrote and illustrated and clearly has more talent than should be allowed for one human.

Methinks this coloring-book craze for adults has gotten way out of hand, and it was questionable to begin with. Now we have Die Hard: The Authorized Coloring and Activity Book welcoming itself to the party, pal, and it is at once a coattails-riding cash grab for 20th Century Fox and a knowing parody of the fad by stand-up comedian Doogie Horner, who wrote and illustrated and clearly has more talent than should be allowed for one human.

Much more fun is to be had. Borseti could have done a better job in editing the conversations of the few people who are so long-winded, they venture into unrelated tangents. For example, I don’t care what the director of

Much more fun is to be had. Borseti could have done a better job in editing the conversations of the few people who are so long-winded, they venture into unrelated tangents. For example, I don’t care what the director of