An alcohol-bloated Richard Burton (The Medusa Touch) is Father Lamont, who leaves his father’s junk empire in Watts to perform meandering exorcisms in Latin America. When his latest dispossession goes up in smoke, quite literally, he’s summoned to the Vatican not for a swift punishment — probably a transfer to a boys’ home in Wisconsin — but instead to find out the truth about a disgraced Father Merrin (Max von Sydow, Never Say Never Again) from the first film.

An alcohol-bloated Richard Burton (The Medusa Touch) is Father Lamont, who leaves his father’s junk empire in Watts to perform meandering exorcisms in Latin America. When his latest dispossession goes up in smoke, quite literally, he’s summoned to the Vatican not for a swift punishment — probably a transfer to a boys’ home in Wisconsin — but instead to find out the truth about a disgraced Father Merrin (Max von Sydow, Never Say Never Again) from the first film.

Regan MacNeil (Linda Blair, Airport 1975), who’s bloated as well — possibly from cocaine — is back also, of course. We learn that since her exorcism she now loves to tap-dance in a shirt that showcases the underside of her breasts, usually before her sessions at Dr. Gene Tuskin’s (Louise Fletcher, 1987’s Flowers in the Attic) very John Boorman-esque — i.e., lots of sharp glass and curved mirrors — research clinic. There, even though she’s buried the events of her brutal exorcism deep in the past, the damn scientific curiosity of Tuskin brings ol’ Pazuzu back to the forefront once again.

While all that is going on, Lamont goes to Africa to hang out with James Earl Jones (Allan Quatermain and the Lost City of Gold), who sits lonesomely in a throne, fully clad in a hilarious life-sized locust costume, complete with a big bug-eyed mask.

Director John Boorman’s clunker of a continuation — hot on the well-booted Exterminator heels of 1974’s Zardoz — is something people mostly watch either out of sick curiosity or general masochism. There are a few Exorcist II: The Heretic apologists out there, and every single one I’ve met is a chunky dude in a fake Tommy Bahama shirt who’ll corner you at a party, explaining with frothing reasoning why you — and most of cinematic academia in general — are morally wrong in your tepid dislike of the sequel.

Director John Boorman’s clunker of a continuation — hot on the well-booted Exterminator heels of 1974’s Zardoz — is something people mostly watch either out of sick curiosity or general masochism. There are a few Exorcist II: The Heretic apologists out there, and every single one I’ve met is a chunky dude in a fake Tommy Bahama shirt who’ll corner you at a party, explaining with frothing reasoning why you — and most of cinematic academia in general — are morally wrong in your tepid dislike of the sequel.

But, for once, most people are right: With the exception of Ennio Morricone’s typically gorgeous score, there’s not much to recommend here. Each progressive scene sillier than the last, Exorcist II manages to turn Satan from a monstrous representation that is Legion to a confusing swarm of African locusts with a taste for yummy psychic powers and tasty fields of grain. Obviously, whatever “good film” that was supposedly here got lost in a parade of big egos and bad ideas.

In the special features, even Linda Blair vehemently admits that this isn’t the film she signed up to do, but, then again, she starred in Roller Boogie. That ought to tell you something right there. —Louis Fowler

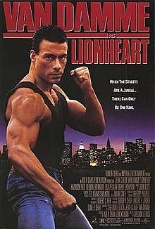

Based on a story and screenplay by action star, martial artist and Tostitos spokesperson Jean-Claude Van Damme,

Based on a story and screenplay by action star, martial artist and Tostitos spokesperson Jean-Claude Van Damme,

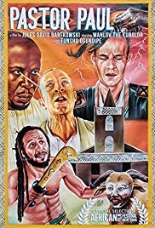

The cinema of Ghana and Nigeria — referred to colloquially and collectively as Nollywood — is best known for its low-budget goofy actioners and laughable melodramas, but there is very much a frightening side to their filmmaking: the ominous atmosphere and existential dread of their many demon-possession films. Forget

The cinema of Ghana and Nigeria — referred to colloquially and collectively as Nollywood — is best known for its low-budget goofy actioners and laughable melodramas, but there is very much a frightening side to their filmmaking: the ominous atmosphere and existential dread of their many demon-possession films. Forget