In 1981, my fifth-grade homeroom teacher postponed class to warn us about a clown seen around Oklahoma City school playgrounds. “If he offers you candy or stamps with cartoon characters on it, don’t take it!” she said sternly. “It’s laced with acid.”

In 1981, my fifth-grade homeroom teacher postponed class to warn us about a clown seen around Oklahoma City school playgrounds. “If he offers you candy or stamps with cartoon characters on it, don’t take it!” she said sternly. “It’s laced with acid.”

We were scared straight, plus downright scared. Children, parents, teachers and authority figures nationwide were. The clown didn’t exist, but the “satanic panic” did, and kid-friendly tabs of LSD were one whispered method of indoctrination. As Rick Emerson delineate in his new nonfiction book, we have the bestselling “diary,” Go Ask Alice, to thank. Or “thank,” because while the book helped some YA readers, its anonymous author, Beatrice Sparks, lived on lies to fuel a delusional ego and desperate need for attention, no matter the lives she destroyed and discarded along the way.

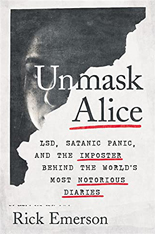

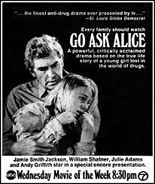

I’ve never read Go Ask Alice or seen the 1973 Emmy-nominated telepic it spawned, starring William Shatner and Andy Griffith. But being familiar with both and living through the resulting hysteria that pilloried everything from rock music to Dungeons & Dragons, Emerson’s Unmask Alice: LSD, Satanic Panic, and the Imposter Behind the World’s Most Notorious Diaries held an undeniable lure. It’s unmissable.

Published in 1971, Go Ask Alice recalled a normal suburban teenage girl’s descent into drugs and ultimately death, via the journal entries she left behind. America was horrified — and gripped. The big problem is, it was all made up, which Sparks failed to inform her publisher, not that the publisher did anything about all the red flags. The bigger problem is, she didn’t stop there.

Published in 1971, Go Ask Alice recalled a normal suburban teenage girl’s descent into drugs and ultimately death, via the journal entries she left behind. America was horrified — and gripped. The big problem is, it was all made up, which Sparks failed to inform her publisher, not that the publisher did anything about all the red flags. The bigger problem is, she didn’t stop there.

Emerson uses Unmask Alice as a triple-purpose biography, charting three lives: that of Sparks; her book, formed from such external cultural forces as Art Linkletter, Charles Manson and Richard Nixon; and poor Alden Niel Barrett, whose abrupt existence was essentially stolen by Sparks for her family-wrecking follow-up. While Emerson does a terrific job in chasing each inexorably linked strand to its end, sharing Barrett’s story — and restoring the reputation of him and his parents — appears to hold the most amount of passion for the author.

Emerson’s hit-the-pavement research keeps Unmask Alice grounded in facts while a fiction-like knack for storytelling never fails to drive you forward. He employs what I call “the Dan Brown method” of structuring chapters, often limiting them to a super-short three or four pages. That way, to paraphrase Lay’s Potato Chips tagline, betcha can’t read just one. I sure couldn’t. —Rod Lott