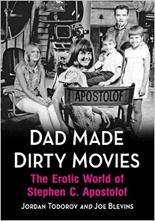

Jordan Todorov’s 2011 documentary, Dad Made Dirty Movies, is a wonderful introduction to one of cult film’s best-kept secrets. But Todorov’s new book on the topic, Dad Made Dirty Movies: The Erotic World of Stephen C. Apostolof, is even better. Although the ideal is to consume both media, 58 minutes face a sheer disadvantage against 336 pages.

Jordan Todorov’s 2011 documentary, Dad Made Dirty Movies, is a wonderful introduction to one of cult film’s best-kept secrets. But Todorov’s new book on the topic, Dad Made Dirty Movies: The Erotic World of Stephen C. Apostolof, is even better. Although the ideal is to consume both media, 58 minutes face a sheer disadvantage against 336 pages.

Written with Joe Blevins and published by McFarland & Company, the book serves as not just a full biography of Apostolof, but the definitive source of information on this unheralded sexploitation pioneer. Even in death, Apostolof continues to live in Ed Wood’s shadow, thanks to their partnership on a handful of films — most notably, 1965’s immortal Orgy of the Dead. Todorov’s work goes a long way in restoring the proper amount of luster to Apostolof’s contributions.

Tracing his transformation from Bulgarian by blood to vulgarian by trade, the book functions best once Apostolof starts making softcore skinflicks. However, don’t dare skip the initial few chapters, because he led quite a life before becoming an off-color/off-Hollywood director, from working for tips as a whorehouse piano player to being sentenced to a concentration camp — all before fleeing his homeland for a fresh start in America.

With Orgy of the Dead marking his directorial debut, the riotous stories from behind the camera are, naturally, like something out of Ed Wood (a biopic that raised Apostolof’s ire, by the way, upon not being invited to take part and not being recognized himself). The contrast of the two men is fascinating, with Apostolof all business and the total pro, and Wood a full-blown alcohol constantly teetering — literally and metaphorically — toward a sad, self-made demise.

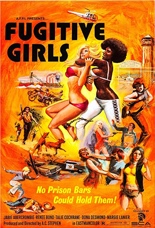

Sure, the thrice-married Apostolof had his failings, too, but they were largely about his inability to financially plan for the future, especially after the market for his breasty brand of bread-and-butter dried up with the proliferation of hardcore pornography. Today, more eccentric cineastes continue to discover and celebrate the relative joys of Fugitive Girls and College Girls Confidential, but in Apostolof’s time, the life for these films was fleeting — petering out shortly after viewers’ collective refractory period.

Despite carrying over the documentary’s title, the book is not framed from the Apostolof children’s point of view, although they certainly provide memories, clear up misinformation and dispel rumors. I found myself envious of son Steve, entering puberty as he visits the set of Dad’s Lady Godiva Rides, a vehicle for the buxom blonde Marsha Jordan.

Despite carrying over the documentary’s title, the book is not framed from the Apostolof children’s point of view, although they certainly provide memories, clear up misinformation and dispel rumors. I found myself envious of son Steve, entering puberty as he visits the set of Dad’s Lady Godiva Rides, a vehicle for the buxom blonde Marsha Jordan.

Film by film, milestone after milestone, Todorov and Blevins tell their subject’s story with reserved reverence — unclouded by rose-colored fanboy glasses — and a fair amount of good humor. Some of the funny bits sneak up on the reader: “[Drop-Out] composer Jaime Mendoza-Nava provided another part-Latin, part-Muzak score. This time, he was billed as J. Mendozoff, a pseudonym that sounds like an over-the-counter sleep aid.” Other instances are more expected, but no less effective: “There are several unproduced Wood screenplays from this era whose titles tell you all you need to know about their contents: The Teachers, The Basketballers, The Airline Hostesses. You don’t need to read them to guess that they respectively concern teachers, basketballs and airline hostesses screwing their brains out.”

With more than 100 photos throughout, Dad Made Dirty Movies closes with a novel appendix offering a peek behind the curtain: two outlines for Apostolof’s never-realized The Immoral Artist, all of four combined pages. You don’t need to read it to guess that it concerns an artist who wants to screw his brains out. —Rod Lott

Really glad you enjoyed it! The time and attention Jordan took, and the effort of over a decade really shows. I’m biased possibly as Stephen’s son, but I’m glad the full story is out and available now, and maybe Jordan can get some sleep finally!