Thirtysomething Canadian filmmaker G. Patrick Condon excels at procrastinating — so much so that he’s squandered the money intended for his latest feature, a slasher film. Fearing investors’ kneecap-breaking action for his fraudulent inaction, the possibly alcoholic director has no choice but to make his movie, pronto.

Thirtysomething Canadian filmmaker G. Patrick Condon excels at procrastinating — so much so that he’s squandered the money intended for his latest feature, a slasher film. Fearing investors’ kneecap-breaking action for his fraudulent inaction, the possibly alcoholic director has no choice but to make his movie, pronto.

Because desperate times call for desperate measures, he rents a three-story house in the country and on the cheap; wires closed-circuit cameras in every nook and cranny, Big Brother-style; and requires the cast to live there during the weeklong shoot. That edict is especially curious since Condon considers actors to be “vile human beings.” No wonder he hires himself to play the killer.

The trick of Incredible Violence is Condon isn’t playing at all; he’s snapped under pressure and prepared to slaughter his cast members for the good of the project. Actually, Incredible Violence has another trick waiting: Its director is also G. Patrick Condon. What I didn’t realize until later, however, is that the Condon of the movie within the movie isn’t really Condon; he’s played by Stephen Oates (TV’s Frontier).

The trick of Incredible Violence is Condon isn’t playing at all; he’s snapped under pressure and prepared to slaughter his cast members for the good of the project. Actually, Incredible Violence has another trick waiting: Its director is also G. Patrick Condon. What I didn’t realize until later, however, is that the Condon of the movie within the movie isn’t really Condon; he’s played by Stephen Oates (TV’s Frontier).

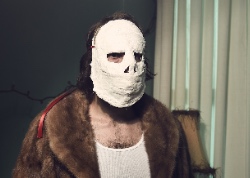

Part of me wonders if watching would be any less of a meta-on-meta mindfuck knowing that information in advance, but I have my doubts, because Incredible Violence is pretty crazy as is, thanks to Oates’ performance as the master manipulator in the attic. Pulling the strings on his own Milgram experiment, his Condon pecks new scenes on the fly, sending them to be spit from dot-matrix printers in each room. His unpaid actors do his spurts of his bidding 24/7 and improvise the rest. When his narrative needs advancing, Condon emerges only to murder, adding a crude papier-mâché theater mask to his ensemble of fur coat and increasingly soiled undershirt.

Although it may not look or sound like it, Incredible Violence intends to disturb and delight, with Condon — the real one, mind you — veering into scenes of the darkly comic and transparently savage with little forewarning. Too bad the performers’ conversations in between are drawn-out to the point of being too conversational — the result of a slack pace and, I suspect, actual improv. Love it or hate it, the film is its own thing: mumblegore. —Rod Lott