The cinema of Ghana and Nigeria — referred to colloquially and collectively as Nollywood — is best known for its low-budget goofy actioners and laughable melodramas, but there is very much a frightening side to their filmmaking: the ominous atmosphere and existential dread of their many demon-possession films. Forget The Exorcist, Rosemary’s Baby, whatever … Ghana and Nigerian filmmakers have them beaten and beaten brutally.

The cinema of Ghana and Nigeria — referred to colloquially and collectively as Nollywood — is best known for its low-budget goofy actioners and laughable melodramas, but there is very much a frightening side to their filmmaking: the ominous atmosphere and existential dread of their many demon-possession films. Forget The Exorcist, Rosemary’s Baby, whatever … Ghana and Nigerian filmmakers have them beaten and beaten brutally.

Maybe it’s because they still fear Satan in a way that Westerners (lamentably) don’t anymore, but regardless, their horror epics featuring demonic witch doctors, torso-shaking, eye-rolling vessels and sweaty preachers calling on Jesus to get rid of that vile creature tend to leave audiences praying for their own soul by the time the credits roll.

But then you’ve got to deal with a sequel … or two … or three …

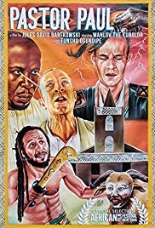

It’s a trend that I’m surprised took American filmmakers so long to latch onto, but auteur Jules David Bartkowski, armed with a camera, a white suit and about 100 bucks or so traveled to this foreign land, gathering the biggest names in (regional) African cinema — Wanlov the Kubolor, Funsho Ogundipe and Lady Nancy Jay, to name a few — and actually made a pretty good first attempt at introductory cinematic diplomacy.

Bartkowski is Benjamin, a mathematician working on African drum rhythms and their supposed equations. When sitting in a bar one afternoon, he’s talked into starring as a white ghost in a film called Pastor Paul. During the filming, however, he goes into a strange trance and when the eccentric director yells cut, Ben can’t remember anything. People tell him he’s possessed, so he travels to a nearby town to hook up with the area witch doctor, and then it gets truly bizarre — but in a financially responsible way, making it even more scary.

Bartkowski is Benjamin, a mathematician working on African drum rhythms and their supposed equations. When sitting in a bar one afternoon, he’s talked into starring as a white ghost in a film called Pastor Paul. During the filming, however, he goes into a strange trance and when the eccentric director yells cut, Ben can’t remember anything. People tell him he’s possessed, so he travels to a nearby town to hook up with the area witch doctor, and then it gets truly bizarre — but in a financially responsible way, making it even more scary.

While many fish-out-of-water films use a certain sense of xenophobia to get their paranoid feelings of danger and despondency across, this film mostly avoids that; surprisingly, mostly everyone in Pastor Paul, from the little kids following the characters around to the long stretch of Christian preaching, is just doing their thing and Benjamin is caught in the middle of it, walking along, letting them tell their stories, letting the audience experience what he does.

Sure, he’s shaking and convulsing around them, stricken by evil creepy crawlies, to bring it all back to the main story, but it’s the moments in between that are infinitely more interesting, to explore the souls of the friends (and enemies) he’s just made, sitting around talking and enjoying bowl after bowl of fufu with his grimy fingers.

But even more interesting is instead of bringing American techniques to Ghana and Nigeria, the filmmakers used theirs, the Africans, as a way to tell a compelling enough story, filled with plenty of strange tangents and obscure jokes to keep both Hollywood and Nollywood viewers both intrigued and waiting for parts two, three and four, which we’re promised is coming, to great terror and foreboding. —Louis Fowler