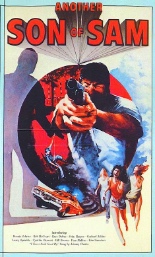

If David Berkowitz, the real-life Son of Sam, actually did receive his orders to kill from a dog, that would make more sense than Another Son of Sam, a bonkers exploitation thriller that trades on the murderer’s media-friendly moniker, but otherwise is unrelated. Not for nothing was this tabloid-tainted obscurity the one and only stab at directing, screenwriting, producing, editing and casting by Dave A. Adams, stuntman of William Grefé’s Whiskey Mountain.

If David Berkowitz, the real-life Son of Sam, actually did receive his orders to kill from a dog, that would make more sense than Another Son of Sam, a bonkers exploitation thriller that trades on the murderer’s media-friendly moniker, but otherwise is unrelated. Not for nothing was this tabloid-tainted obscurity the one and only stab at directing, screenwriting, producing, editing and casting by Dave A. Adams, stuntman of William Grefé’s Whiskey Mountain.

After three minutes of ellipses-ridden titles commemorating the exploits and body counts of such all-star serial killers as Jack the Ripper, Charles Starkweather and Richard Speck, Another Son of Sam presents a live performance by the Tom Jones-esque singer Johnny Charro (as himself) at the Treehouse Lounge, which has as much bearing on the hour that follows as all the front-loaded discussion of waterskiing: zilch. Just get used to that; Adams has no idea how to set up a story, so the viewer will be unable to determine the main character. I thought I knew, but learned — after my second viewing, no less — that the policeman I assumed was the lead was actually two officers who not only look alike, but have similar-sounding names. To say that the “FLUSH OLD MEDICINES DOWN THE TOILET” sign spotted in early scenes is more prominent than any of its surrounding performers is hardly an exaggeration.

Therefore, there is no lead role — not even the titular madman, Harvey! Until the climax, such as it is, we glimpse him only as a set of feet or hands or eyes in extreme close-up, like the creature in Creepshow’s segment of “The Crate.” Strangling an orderly with a telephone cord and clocking a lady doc into a coma, Harvey escapes a mental institution, where a treatment of shock therapy literally jolts into a willy-nilly killing spree. His reign of terror occurs mostly in a girls’ college dorm — one well-populated, despite it being spring break. Once Harvey slays one of its residents (who stole $500 from the administration building, so she sorta deserves it, the film suggests), the police call in the local S.W.A.T. team, whose members perform on the level of S.H.I.T., making for an awkwardly inert action sequence of roughly 30 minutes. (At least the S.W.A.T. commander is entertaining in mispronouncing super-simple words in a super-Southern drawl: “window” –> “wind-uh.”)

Therefore, there is no lead role — not even the titular madman, Harvey! Until the climax, such as it is, we glimpse him only as a set of feet or hands or eyes in extreme close-up, like the creature in Creepshow’s segment of “The Crate.” Strangling an orderly with a telephone cord and clocking a lady doc into a coma, Harvey escapes a mental institution, where a treatment of shock therapy literally jolts into a willy-nilly killing spree. His reign of terror occurs mostly in a girls’ college dorm — one well-populated, despite it being spring break. Once Harvey slays one of its residents (who stole $500 from the administration building, so she sorta deserves it, the film suggests), the police call in the local S.W.A.T. team, whose members perform on the level of S.H.I.T., making for an awkwardly inert action sequence of roughly 30 minutes. (At least the S.W.A.T. commander is entertaining in mispronouncing super-simple words in a super-Southern drawl: “window” –> “wind-uh.”)

Amateurs though the performers may be (and they are), their acting is hardly the flick’s defining deficiency. Another Son of Sam sports a color palette as brown as a UPS truck full of UPS uniforms; its straightforward timeline struggles to adhere to a reality as it leaps between cops and collegians; Adams employs slow-motion for no other discernible reason than to elongate the running time over the hour-and-a-nickel mark; his editing choices are so puzzling, they veer toward the experimental (emphasis on “mental”) — and that’s even discounting his head-scratching decision to end virtually every scene with a freeze frame! Why, it’s as if Adams caught the final shot of François Truffaut’s The 400 Blows and thought, “If it works once, why not dozens of times?” Ergo, freeze frames out the wazoo — enough to power a 1982 J. Geils Band single.

In summary, this is a killer no-budget, no-win endeavor lensed in that hotbed of auteurist cinema, North Carolina. Don’t you dare miss it! —Rod Lott