Having written the so-far-definitive book on Eurocrime with 2013’s Italian Crime Filmography, film critic Roberto Curti sticks within Italy’s borders — and the McFarland publishing family — to deliver Italian Gothic Horror Films, 1957-1969. And damned if it isn’t the best book I’ve read on that subgenre, too, despite being much smaller in physical size and page count.

Having written the so-far-definitive book on Eurocrime with 2013’s Italian Crime Filmography, film critic Roberto Curti sticks within Italy’s borders — and the McFarland publishing family — to deliver Italian Gothic Horror Films, 1957-1969. And damned if it isn’t the best book I’ve read on that subgenre, too, despite being much smaller in physical size and page count.

As with that book, Curti tackles the titles individually, year by year, from ’57’s I Vampiri, arguably the boot-shaped country’s first horror film, to the takeover of the giallo. Before doing so, however, his preface serves to break down Italian Gothic’s 10 key elements. The man clearly knows his stuff — and not just because he’s one of the few writers who actually spells Edgar Allan Poe’s middle name correctly, although that certainly goes a long way in credibility.

When you hear the word “filmography,” you might (as I often do) fear the pages will be plagued by heavy, detailed (if not outright droning) plot synopses. Not Curti. He knows cinephiles either are familiar enough with the movies to need only the barest of reminders or haven’t seen them and don’t wish to have them spoiled, so summaries are just that: summaries, and blessedly brief. They’re also contained to a single italicized paragraph for easy skipping, so readers can get right to the meat of each entry: his critical analysis.

Naturally, the more iconic and influential the film, the more Curti has to say about it; for example, I think nothing eclipses Mario Bava’s Black Sunday in terms of weight here, and the author’s essay reflects that. (Although I also often do, Black Sunday is not to be confused with Bava’s Black Sabbath, which coincidentally adorns this volume’s front cover.) Curti singles out another Bava effort, 1963’s The Whip and the Body, as “the quintessential Gothic film — or rather, it looks like it.”

Naturally, the more iconic and influential the film, the more Curti has to say about it; for example, I think nothing eclipses Mario Bava’s Black Sunday in terms of weight here, and the author’s essay reflects that. (Although I also often do, Black Sunday is not to be confused with Bava’s Black Sabbath, which coincidentally adorns this volume’s front cover.) Curti singles out another Bava effort, 1963’s The Whip and the Body, as “the quintessential Gothic film — or rather, it looks like it.”

From legitimate terrors (Nightmare Castle) to goofy pulp (Bloody Pit of Horror) and juvenile tease (The Playgirls and the Vampire), Curti covers all with an essay that dives deeper than even the filmmakers would expect. So in depth does he get, he practically plays P.I. to relate the muddled making of Antonio Margheriti’s Castle of Blood.

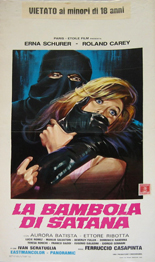

A wealth of poster art and production stills exists to liven up the layout, as well as set mood. It’s one thing to read about the Gothic, but an entirely different experience — meaning enhanced — to read about it as you see illustrative examples, and these films arrived in theaters with some of the most eye-catching, artistically rendered one-sheets in the biz — all heaving bosoms and headless torsos. Barbara Steele fans in particular will have much to rejoice.

And as a whole, lovers of Italian Gothic horror film will find much to praise about Italian Gothic Horror Films, an enjoyably precise, lovingly penned examination of a stylistic wave of cinema that didn’t live long, but endures in an afterlife thanks to digital media, fervid fans and, yes, texts like Curti’s. —Rod Lott