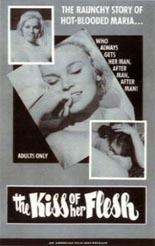

Boasts slut slayer Richard Jennings at the beginning of The Kiss of Her Flesh, “I do a service to all mankind with each jezebel I kill!” Essentially, the exclamation could double as a plot summary for Kiss, the final chapter of Michael Findlay’s depraved, shake-and-ache trilogy. How depraved? We hear the above while he helps himself to the bare breasts of the woman he’s just tire-ironed into strippable submission. But that’s nothing.

Boasts slut slayer Richard Jennings at the beginning of The Kiss of Her Flesh, “I do a service to all mankind with each jezebel I kill!” Essentially, the exclamation could double as a plot summary for Kiss, the final chapter of Michael Findlay’s depraved, shake-and-ache trilogy. How depraved? We hear the above while he helps himself to the bare breasts of the woman he’s just tire-ironed into strippable submission. But that’s nothing.

After the credits sequence, in which the titles are handwritten on pieces of paper cut into lip shapes and placed over a nude female body, Jennings (Findlay himself) resumes his misogynist mission of murder, slaughtering every lady who reminds him of his cheating wife, which is every lady. That includes the one who:

• is tied up in a kitchen and menaced with a lobster claw;

• receives a house call from a “doctor” (Jennings in his “master of disguise” thing) who performs a “thorough examination” on the tooth marks surrounding her no-no hole and prescribes a morning douche, which he’s spiked with acid;

• hitchhikes her way into Jennings’ station wagon, only to be blowtorched for her troubles; and

• performs oral stimulation on Jennings as ordered, which proves deadly because … well, let’s him tell us: “My poisoned semen should take care of you well enough. So long, sucker!”

Jennings is nothing if not quick with the quips. Topping the simple “Burn, slut!” and the “I will slice you in two like a piece of cheese!” threat is this baffler spoken to the aforementioned seafood victim: “We’ll cut away these underpants to more easily get at the sauce!”

Jennings is nothing if not quick with the quips. Topping the simple “Burn, slut!” and the “I will slice you in two like a piece of cheese!” threat is this baffler spoken to the aforementioned seafood victim: “We’ll cut away these underpants to more easily get at the sauce!”

The Kiss of Her Flesh kinda sorta attempts a story, with Jennings being pursued by angry Maria (Uta Erickson, The Ultimate Degenerate) after he offs the best friend of her (incestuous) sister. Maria begins this trip of vengeance directly after introducing her boyfriend (Earl Hindman, aka Wilson of TV’s Home Improvement) to the pleasures of anal beads, because you’ve gotta have priorities. Findlay clearly did: Work out his twisted fantasies on film, at the risk of lucidity and other narrative crutches preferred by moviegoers — or at least those not wearing raincoats. —Rod Lott