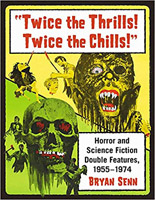

While I am old enough to remember true double features being advertised, I unfortunately am young enough to never have had the good fortune to attend. By “true,” I borrow the criteria used by author Bryan Senn, referring to studios’ or distributors’ intentional pairings, rather than those at the whim of a theater owner or two-for-one reissues. This keeps his book on the subject, “Twice the Thrills! Twice the Chills!”, at a manageable length. So does limiting coverage to the genres and date range set by the book’s subtitle, Horror and Science Fiction Double Features, 1955-1974. Mind you, even with those filters in place, the contents make up yet a still whoppin’ 430-ish pages.

While I am old enough to remember true double features being advertised, I unfortunately am young enough to never have had the good fortune to attend. By “true,” I borrow the criteria used by author Bryan Senn, referring to studios’ or distributors’ intentional pairings, rather than those at the whim of a theater owner or two-for-one reissues. This keeps his book on the subject, “Twice the Thrills! Twice the Chills!”, at a manageable length. So does limiting coverage to the genres and date range set by the book’s subtitle, Horror and Science Fiction Double Features, 1955-1974. Mind you, even with those filters in place, the contents make up yet a still whoppin’ 430-ish pages.

As he did with such previous works as The Most Dangerous Cinema and The Werewolf Filmography, Senn takes a focused look at a niche corner of cult movies and leaves no set of sprockets unchecked. Following an enlightening introduction of how and why the double feature came to be, he takes the reader on a chronological tour of presumably ever cinematic twofer, 147 in all. He not only reviews each picture individually, but even how well the films meshed — or mismatched, “like a schnitzel taco.”

As always, his reviews are as thorough and informed as they are entertaining. While the McFarland & Company book more than delivers as film criticism, I find “Twice the Thrills! Twice the Chills!” to be more valuable as a historical document on two fronts, appropriately enough. The first is simply in preserving the memories of Hollywood’s now-abandoned practice as generously illustrated through movie posters, newspaper ad mats and PR ballyhoo. If the posters and ads are a treat (and they are), perhaps best represented by the conjoining on the book’s cover (the iconic grindhouse one-two gut punch of I Eat Your Skin and I Drink Your Blood), the latter is even more so, represented with such images of such get-’em-in-the-door gimmicks as “zombie eyes” for Plague of the Zombies and a Four Skulls of Jonathan Drake kids’ mask.

The second front is in providing biographical sketches of — and subsequently saluting — largely unsung B-movie “heroes” like Teenagers from Outer Space auteur Tom Graeff (aka Jesus Christ II) or taxi driver Leonard Kirtman, whose double bill of Carnival of Blood and Curse of the Headless Horseman had to the most surreal experiences for theatergoers among all revisited in Senn’s worth-ever-penny wonder. —Rod Lott