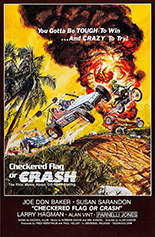

A Filipino version of the Cannonball Run, the Manila 1000 is a three-day, off-road race involving everything from jeeps and dune buggies to stock cars and stocky Joe Don Baker (The Living Daylights) as driver Walkaway Madden. It also features motorcycles — or “motor-sickles,” if you wish to pronounce it as does race promoter Bo Cochran, played by Larry Hagman (TV’s Dallas) in a hat pilfered from Carmen Sandiego’s entry hall.

A Filipino version of the Cannonball Run, the Manila 1000 is a three-day, off-road race involving everything from jeeps and dune buggies to stock cars and stocky Joe Don Baker (The Living Daylights) as driver Walkaway Madden. It also features motorcycles — or “motor-sickles,” if you wish to pronounce it as does race promoter Bo Cochran, played by Larry Hagman (TV’s Dallas) in a hat pilfered from Carmen Sandiego’s entry hall.

Before the start, in a setup soon to be swiped by Safari 3000, a plucky journalist from Stratus magazine (Susan Sarandon, the same year she did The Great Smokey Roadblock) pokes her nose around for a story, so Cochran forces Madden to let her ride shotgun. Dressed in a lumpy-butt jumpsuit that’s less Evel Knievel and more Elvis ’77, Madden is furious, like, “A yucky woman? Phooey!” so you just know they’ll bicker and bitch until they fall into something approximating love or lust. Worry not — we’re spared the sight of a Sarandon/Baker sammie.

Storywise, Checkered Flag or Crash actively works against itself, as if settling to let Harlan Sanders’ boot-scootin’ theme song do all the plotting: “Checkered flag or crash / Goin’ for the heavy green, gonna beat ’em / Checkered flag or crash / There ain’t no in between / So do me right, you damn machine.”

The slight variation from that outline arrives with news of an upcoming stretch of the route suddenly becoming impassable … so Cochran doubles the prize money. This should clear the way for director Alan Gibson (The Satanic Rites of Dracula) to turn in a film that feels faster and more dangerous, yet over and over again, he demonstrates how ill-suited he is for the job.

From Macon County Line’s Alan Vint to Playboy centerfold Daina House as a masked rider, Gibson has all the ingredients within reach to make a rip-roarin’, race-brained hicksploitation pic. Instead, he botches the recipe with confusing staging and editorial choices that are particularly flabbergasting for this subgenre — for instance, slowing down and removing frames from some of the more extreme-speed stunts, which is a technique one level above a photo flipbook.

Plus, with pacing akin to the driving skills of my late, not-so-great stepgrandmother — lay on the accelerator, let up, lay on the accelerator, let up, ad infinitum — you’re better off watching an autocentric film that wastes more gas than it wastes your time. —Rod Lott