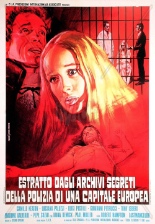

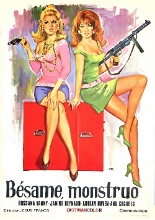

That Awful Dr. Orlof gains a second “F,” but loses usual director Jess Franco, in Orloff Against the Invisible Man, fifth or so in the loosely bound sex-science series, depending on whom you ask.

That Awful Dr. Orlof gains a second “F,” but loses usual director Jess Franco, in Orloff Against the Invisible Man, fifth or so in the loosely bound sex-science series, depending on whom you ask.

Having received vague word that someone has fallen ill at Professor Orloff’s castle, Dr. Garondet (Paco Valladares) wants to get there to render aid, yet requires assistance. Complicating matters is that damn near every villager shudders at the mention of Orloff’s name and refuses to help. Once the good doctor finally arrives, he learns that Orloff’s daughter, Cécile (Brigitte Carva, in her one and only role), sounded the medical alarm under false pretenses: No one there is sick.

Well, not physically, perhaps …

Cécile is concerned about her father’s mental state. However, when Dr. Garondet consults Orloff (Howard Vernon, The Diabolical Dr. Z), the professor says essentially the same about her! Orloff then proceeds to sell Dr. G a lengthy explanation, which we see play out in extended flashback. It involves his latest and greatest experiment: making an invisible man!

Cécile is concerned about her father’s mental state. However, when Dr. Garondet consults Orloff (Howard Vernon, The Diabolical Dr. Z), the professor says essentially the same about her! Orloff then proceeds to sell Dr. G a lengthy explanation, which we see play out in extended flashback. It involves his latest and greatest experiment: making an invisible man!

Orloff created him out of revenge for his colleagues’ years of scorn and insults; director and co-writer Pierre Chevalier (The Panther Squad) created him because having a transparent foil sure cuts down on your monster movie’s budget. Alternately known as Dr. Orloff’s Invisible Monster and too many other titles, the film is full of such rudimentary effects as floating household (castlehold?) items and, increasingly, more prurient ones, like ripping off ladies’ clothing. The only thing more unintentionally amusing than a young women’s roll in the hay with an unseen partner comes at Against’s end, when we get a peekaboo at that see-through rascal. You’ll laugh at the reveal.

You also wouldn’t know Franco was not involved if you happened to miss the credits, because not only does Vernon reprise his Awful role, but Chevalier (purposely or not) imitates Franco through awkward pauses, out-of-focus close-ups, OB-GYN-style gazes and general nonsense. As a nearly harmless lark, this Eurohorror flick of suspect aptitude packs a nutritionally empty wallop to the ol’ pleasure sensors. —Rod Lott

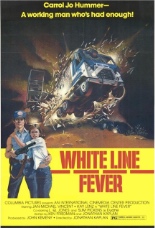

Apologies to Jonathan Kaplan’s

Apologies to Jonathan Kaplan’s

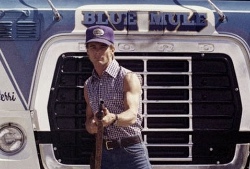

An immediate sequel to the same year’s

An immediate sequel to the same year’s