When you’re jawing about the Old West and its history, the first thing that should be dealt with is all the horrid victimization of the Indigenous people assaulted and murdered by “good” white people, something that still happens to this very day.

So, sorry, John Wayne, Clint Eastwood and Kevin Costner.

That being realized, the second thing most people remember about the Western frontier is the brat-ish fiction and scrubbed nonfiction of the outlaw of outlaws, Billy the Kid. Popularized by mass-media pop culture from the 1930s in movies like The Outlaw to modern-day fare like Young Guns, he has stayed on the hay-baling radar for well over a century.

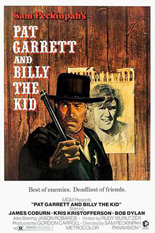

But leave it to hard-drinking, pill-popping and well-regarded director Sam Peckinpah to have his say about the rough-and-tumble legend-crasher with Pat Garrett and Billy the Kid. Although less bloody and violent than Peckinpah’s The Wild Bunch or Bring Me the Head of Alfredo Garcia, this caustically serene 1973 film has a brutally lackadaisical form that makes it his most misunderstood — and endlessly watchable — picture. Hot damn.

Aided by Bob Dylan’s soul-stirring, beautifully written soundtrack, we meet uneasy friends Pat Garrett (tough son of a bitch James Coburn) and William Bonney aka Billy the Kid (baby-faced son of a bitch Kris Kristofferson), as lawman Pat gives Billy six days to leave the country or he’ll take him in, by hook or crook.

After the initial shootout, Billy is jailed. But, being a total badass, he escapes and guns down the law, making a break for some Mexican freedom, only to find Pat and his peacemakers wanting retribution and reprisals.

Knockin’ on heaven’s door, so the song goes …

And really, that’s the whole story: a barren world of post-apocalyptic lawmen who carry phony badges and the demonic crooks who will, in theory, blow the outhouse hinges off the whole place, while everything just peters out with both sides taking the loss. It’s hell on earth — or just plain hell.

Making a case for the well-meaning travelogue on a consistent tour of the underworld, both Coburn and Kristofferson are well-timed to the hellfire rolls of Garrett and the Kid. The Sweetwater flies surrounding Peckinpah’s production include R.G. Armstrong, L.Q. Jones, Slim Pickens, Jason Robards and Harry Dean Stanton — a real murderers’ row of outlaws, banditos and horse thieves.

But what truly makes this sauntering joyride all more the incomparable is Dylan’s casting as the enigmatic Alias, a no-name seer who has no joy and no pain in the Western setting, singing mournful hymns as the dust settles in the blazing distance. Though his theatrical roles have always been very hit (Masked and Anonymous) and very miss (Hearts of Fire), he always plays the soulful conductor of a soulless orchestra, which always makes him so interesting, and that all fictionally started here. His tunefully rustic soundtrack ruefully ranks up there with his other aural masterpieces.

In the end, Pat Garrett and Billy the Kid is the meaty type of transcendent Western that is criminally thoughtful, beautifully violent and, like most of Peckinpah’s films, tragically raw to the bone. It’s all there in the bleeding marrow, taking it all out of cinematic purgatory and into pure filmic heaven. —Louis Fowler