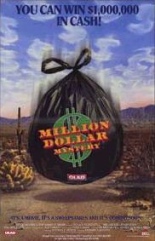

No movie ever should start with Eddie Deezen driving a pink jalopy, Tom Bosley wearing a cowboy hat, and/or three blondes with a burning need to urinate. (It’s in Cahiers du Cinéma. Look it up.) That’s Million Dollar Mystery in a nutshell — emphasis on the “nut,” waka waka waka! When people say, “You couldn’t pay me a million dollars to see that,” they mean this legendarily lethal Dino De Laurentiis/Glad Bag sinkhole, which offered viewers a chance to win just that with admission. It grossed $989,033. Oh, well!

No movie ever should start with Eddie Deezen driving a pink jalopy, Tom Bosley wearing a cowboy hat, and/or three blondes with a burning need to urinate. (It’s in Cahiers du Cinéma. Look it up.) That’s Million Dollar Mystery in a nutshell — emphasis on the “nut,” waka waka waka! When people say, “You couldn’t pay me a million dollars to see that,” they mean this legendarily lethal Dino De Laurentiis/Glad Bag sinkhole, which offered viewers a chance to win just that with admission. It grossed $989,033. Oh, well!

At a roadside diner, Bosley keels over after eating chili, but not before telling fellow eaters that he’s hidden $4 million among four places, and it’s theirs if they can find it. Joining in this madcap rush for cash are Deezen, comedian Rick Overton, Playboy Playmate Penny Baker and no one else famous. At least they got Bill Murray to appear the mentally unstable Vietnam vet, Slaughter Buzzárd. Oh, my bad — they couldn’t afford him. That’s Rich Hall, he of “Sniglets” fame.

Like It’s a Mad, Mad, Mad, Mad World; Scavenger Hunt; or Rat Race, it’s a cast-crowded, cross-country, comedic chase, wherein greed gets the best of everyone involved. Unlike It’s a Mad, Mad, Mad, Mad World; Scavenger Hunt; or Rat Race, it has not one genuine laugh. In fact — spoiler alert! — it’s fucking stupid. It gave my DVD player an extra chromosome.

Like It’s a Mad, Mad, Mad, Mad World; Scavenger Hunt; or Rat Race, it’s a cast-crowded, cross-country, comedic chase, wherein greed gets the best of everyone involved. Unlike It’s a Mad, Mad, Mad, Mad World; Scavenger Hunt; or Rat Race, it has not one genuine laugh. In fact — spoiler alert! — it’s fucking stupid. It gave my DVD player an extra chromosome.

Sadly, this was the last film of director Richard Fleischer (Fantastic Voyage) and stuntman Dar Robinson; the latter actually died for this junk. To add insult to injury, the filmmakers dedicate the work to him — but in quotes, as if insincere — while “comedy” duo Mack & Jamie, two of the least funny people on the planet, improv. The only thing more embarrassing is Kevin Pollak’s constant, cringe-worthy celebrity impressions. Scratch that: Worse is that this represents proof I watched the damn thing. —Rod Lott

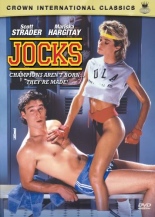

Our nominal hero here is “The Kid” (Scott Strader), who’s supposed to be a wildly charismatic party animal, but more closely resembles a crude, lazy, narcissistic prick with severe emotional problems. We’re led to believe he’s the glue required to keep his ragtag tennis team on their improbable winning streak, but all we actually see him do is take them out to a series of increasingly sleazier bars. At some point, future Emmy/Golden Globe-winner Mariska Hargitay shows up in order to be his love interest, but you’ll be too pre-occupied trying to figure out if she’s had any plastic surgery between then and now to notice how superfluous her character actually is.

Our nominal hero here is “The Kid” (Scott Strader), who’s supposed to be a wildly charismatic party animal, but more closely resembles a crude, lazy, narcissistic prick with severe emotional problems. We’re led to believe he’s the glue required to keep his ragtag tennis team on their improbable winning streak, but all we actually see him do is take them out to a series of increasingly sleazier bars. At some point, future Emmy/Golden Globe-winner Mariska Hargitay shows up in order to be his love interest, but you’ll be too pre-occupied trying to figure out if she’s had any plastic surgery between then and now to notice how superfluous her character actually is.

Although they both proclaim to love one another deeply, their time apart is the beginning of the end. And good for him, because no sex would be worth being hitched to someone as brick-stupid as Lola. As Jim Dale’s theme song goes, she’s “pretty crazy, dizzy as a daisy,” with a squeaky voice that makes Teresa Ganzel seem like a Rhodes Scholar by comparison. “Darling, what’s a Puerto Rican?” asks Lola, who literally can’t remember how to look before crossing the street.

Although they both proclaim to love one another deeply, their time apart is the beginning of the end. And good for him, because no sex would be worth being hitched to someone as brick-stupid as Lola. As Jim Dale’s theme song goes, she’s “pretty crazy, dizzy as a daisy,” with a squeaky voice that makes Teresa Ganzel seem like a Rhodes Scholar by comparison. “Darling, what’s a Puerto Rican?” asks Lola, who literally can’t remember how to look before crossing the street.

But she mistakenly believes that he has been kidnapped, and refuses to pay. The plot gets more convoluted with twists and turns that eventually involve Sherman Helmsley and Danny DeVito as a morgue attendant with a hard-on for saving things removed from people’s rectums and

But she mistakenly believes that he has been kidnapped, and refuses to pay. The plot gets more convoluted with twists and turns that eventually involve Sherman Helmsley and Danny DeVito as a morgue attendant with a hard-on for saving things removed from people’s rectums and

The answer: Because Arthur Penn was awesome.

The answer: Because Arthur Penn was awesome.