In the ’90s-era rumpus-room of near-subhuman Oklahoma City, if you were a somewhat competent cinephile, your main outlet of cult oddities and underground filth was the long-gone Kaleidoscope Video on MacArthur Boulevard.

Here, as a disciple of Danny Peary’s Cult Movies, I typically rented his recommendations, at least the ones I could find. One was Privilege, the mid-’60s film promising the revolution would be sponsored by the British government. Sadly, as it began, the tape snapped, leaving me with a broken VHS cassette deemed irreplaceable.

Recently, I spotted Privilege in one of the always-stellar Kino Lorber sales, and snatched it up, sight unseen after 25 years. After watching it for a third time since purchasing, I have to say the wait was completely worth it. More than worth it.

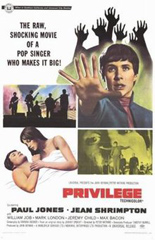

In the fab-gear-beat 1960s of the near modernly dystopic future, the top teen idol is Steven Shorter (Manfred Mann lead singer Paul Jones), a dyspeptic sort with a chip on his shoulder. Though he is the idol of most teens, instead of rising to the top of the pops, he is instead crashing the controlled charts of the British government for their totalitarian means.

It’s a switched-on nightmare.

Shot in a faux-documentary style, Shorter’s stage show is one of guilt and repentance, with assigned bobbies bashing his adoring fans in the head. As the government sells him out to the corporation factions — most notably for the fall apple-picking season, making sure everyone eats six apples a day — Shorter is fine for the most part. But when the church tries to convert the British public to view him as a near-messiah, Shorter has a mental breakdown that leads nowhere but down, down, down.

Directed by the masterfully rueful Peter Watkins (of The War Game and Punishment Park fame), he brings Beatlemania to the masses — an act like a precursor to the cult of personality that rages to this day. A total indictment of British society and its hold on the youth market, it’s pop-art terror told with a twinge of the blackest humor.

As Shorter, Jones is more than suitable as the put-upon rock star, with Vogue it girl Jean Shrimpton as his somewhat love interest who seems to understand him. Together, they’re an aloof couple not meant to exist in this world.

While Privilege‘s pop-art world might seem orderly, quaint and tidy, at it source it’s a mean, ghostly and utterly prescient look at the modern iconoclasts who have traded their humanity for a recording contract, proving that the devil is deep in the details. —Louis Fowler