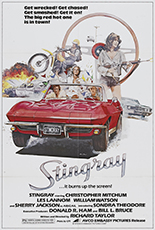

Let Stingray be a lesson to all coke dealers who, fleeing a deadly vice raid, temporarily hide $1 million worth of smack in a little red Corvette overnight: The used car lot is under no obligation to protect your contraband inventory.

Let Stingray be a lesson to all coke dealers who, fleeing a deadly vice raid, temporarily hide $1 million worth of smack in a little red Corvette overnight: The used car lot is under no obligation to protect your contraband inventory.

Hoping the heat has cooled, the criminal duo (The Sword and the Sorcerer’s William Watson and Stewardess School’s Bert Hinchman) returns the next morning to retrieve the stash, only to witness the titular convertible being purchased by fine young pals Al (Christopher Mitchum, Savage Harbor) and Elmo (Les Lannom, Shoot to Kill). As was the wont of Smokey and the Bandit imitators, a movie-long chase ensues.

Distinct and memorable, Al and Elmo’s pursuers soon number four with the addition of a greasy hit man (Cliff Emmich, Hellhole) and their lady boss (Sherry Jackson, The Mini-Skirt Mob); the latter is disguised as a nun, prefiguring Shirley MacLaine and Marilu Henner’s cloak of choice in Cannonball Run II. (Speaking of clothing, Elmo spends the movie in a bumblebee-striped shirt made of terrycloth, like a cheap child’s bathrobe.) Throw the cops in there, too, and we lose count of the amount of heat on Al and Elmo’s combined tail.

Dollar for dollar, minute by minute, of the many Bandit also-rans, Stingray ranks among the finest — or at least the “funnest.” Well-executed in the same can-do manner as the tragically few films of H.B. Halicki (1974’s Gone in 60 Seconds), it wastes no time going from zero to 60, as the characters encounter various rural rats, hippies, the occasional bulldozer, a student driver, Playboy Playmate Sondra Theodore and, in a rather inventive bit, an ill-timed trip through an automatic car wash.

Somehow the only feature for writer and director Richard Taylor, Stingray continuously plows forward as a four-cylinder good time, due to his keen sense for stunts and the ability to stage them. Part of what makes them so impressive is the palpable danger viewers can sense as people jump out of the way of speeding vehicles at the Very Last Second, or as a motorcycle zig-zags through the woods in a sequence so immersive, you can smell the exhaust. There’s something admirable about Taylor’s casual depiction of recklessness, with such juxtaposition as live grenades thrown at farmers while the soundtrack busies itself with hoedown circus music — and admire it I do, as a scrappy yet standout example of ’70s car-fetishization cinema where whoever sits behind the wheel matters not a lick. —Rod Lott