Deep within the Grand National Forest live – well, for the time being – three redneck brothers:

Deep within the Grand National Forest live – well, for the time being – three redneck brothers: Larry, Darryl and Darryl Monroe, Ezra and Benny. They’re about to be displaced, thanks to a new campground opening in time for the July 4 holiday weekend. Monroe (William Kerwin, Blood Feast), the only sibling literate enough to read the sign that indirectly serves as their eviction notice, has other plans: “Ezra, we’re gonna run ’em off. This time, we ain’t leavin’.”

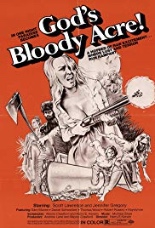

Efficiently, that’s the first scene of God’s Bloody Acre, and should be all the plot a hickspolitation flick needs: hillbillies vs. capitalists, as Monroe, the old one with suspenders; Ezra (Daniel Schweitzer, of the director’s 1977 follow-up, Tomcats, and nothing else), the one with facial hair and neck hankie; and Benny (Sam Moree, ditto), the Afro-sporting, simpleminded mute who sheds tears when tree limbs are felled, band together to take their revenge. Part of their plan involves chucking rocks at the guy operating the Caterpillar bulldozer. Part of that plan does not involve said operator getting bisected by the blade, but that’s what happens. Upon this grisly discovery, one of the dead guy’s hard-hatted colleagues asks if this means they “can knock off early.”

Curiously, director Harry E. Kerwin (Barracuda) and his co-writer/co-producer, actor Wayne Crawford (aka Jake Speed), dilute the film’s initial intent of pure, unfiltered revenge by adding buckets of subplots — one of which even overtakes that of the Monroe clan: the one featuring Crawford.

Curiously, director Harry E. Kerwin (Barracuda) and his co-writer/co-producer, actor Wayne Crawford (aka Jake Speed), dilute the film’s initial intent of pure, unfiltered revenge by adding buckets of subplots — one of which even overtakes that of the Monroe clan: the one featuring Crawford.

Under the nom de plume of Scott Lawrence, Crawford plays Scott, a proto-Jerry Maguire who impulsively quits the white-collar job he doesn’t believe in and hops on a motorcycle, searching for an America he doesn’t find anywhere. But, after his ride breaks down, he does find love — or at least lake sex — with Leslie (Jennifer Stock, Shriek of the Mutilated), a young woman in a VW Bus, fleeing an abusive relationship. Viewers see their individual backstories, as we do for the two occupants of an RV: a virulent racist (Robert Rosano in his lone credit) and his long-suffering wife (Suzanne Robinson of the director’s adults-only Sweet Bird of Aquarius).

We expect not all of these travelers will make it to the final reel; we do not expect to get to know them more than the siblings. As God’s Bloody Acre progresses — rape, murder, it’s just a shot away — Monroe and company becomes less like characters and more like faceless villains. File Harry E. Kerwin’s decision to do so not under “abject failure,” but “missed opportunity.” The finished film is unique enough in that its Greenpeace-friendly themes give us a glimpse into what might have happened if Rachel Carson had made The Hills Have Eyes instead of Wes Craven. —Rod Lott