In a book we highly recommend, former NASA employee Thomas Kent Miller takes us on every cinematic journey to the red planet, film by film, from the silents to today. And now, for his hat trick of a Flick Attack Guest List, the author takes us on yet another cinematic journey of a different kind: through the photos and illustrations that you won’t find in the finished book! Once more, the volume’s loss is your eyes’ gain. Time to blast off!

In a book we highly recommend, former NASA employee Thomas Kent Miller takes us on every cinematic journey to the red planet, film by film, from the silents to today. And now, for his hat trick of a Flick Attack Guest List, the author takes us on yet another cinematic journey of a different kind: through the photos and illustrations that you won’t find in the finished book! Once more, the volume’s loss is your eyes’ gain. Time to blast off!

My book Mars in the Movies: A History is a ship that has sailed. Still, I can daydream. This is my third Guest List for the site of coulda/woulda/shouldas for graphics that I would have liked to have included in the book, but it was not practical.

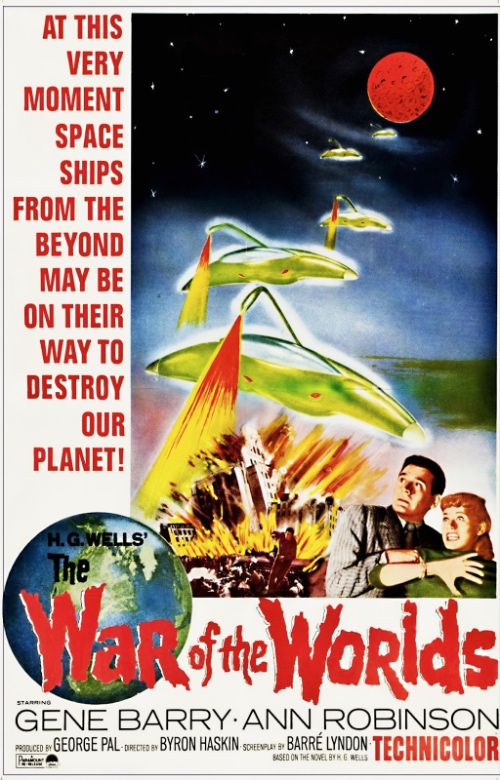

1. Twelve years after its initial release in 1953, The War of the Worlds was re-released. This is its principal re-release one-sheet. I like this poster.

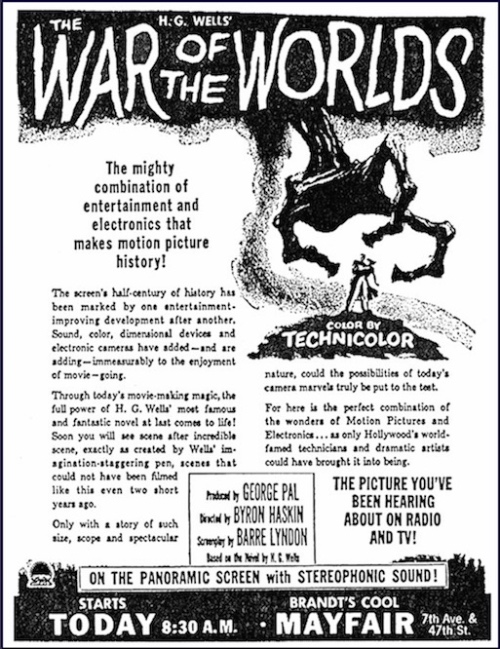

2. Visual effects expert Robert Skotak says, “Some theaters in L.A. and New York projected The War of the Worlds at 1.85:1 with the proper 1.85:1 mask. The ads in newspapers featured the words ‘in widescreen’ [or ‘in panoramic screen’].” This was during the era of CinemaScope and the like. Here’s a print newspaper ad for the original engagement of The War of the Worlds at the Mayfair theater in Times Square, New York City …

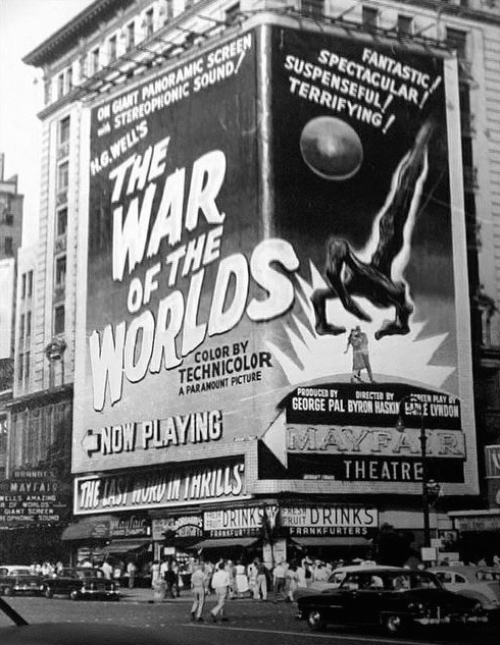

3. … and the Mayfair theater itself wrapped up like a Christmas present! They don’t do movie promotions like they used to!

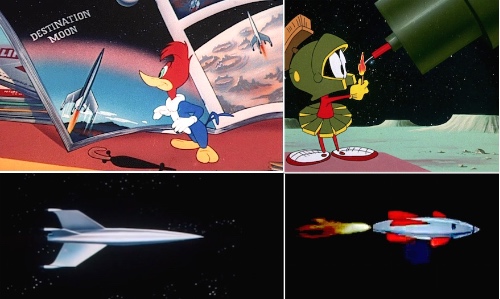

4-7. In the groundbreaking 1950 film Destination Moon, there is a scene early on showing a roomful of potential corporate sponsors gathered to hear a sales pitch as to why they should bankroll sending a rocket to the moon. Jim Barnes, who’s betting his reputation on the expedition, shows a colorful short Woody Woodpecker cartoon that helps seal the deal. I am venturing an intelligent guess that Chuck Jones’ space-based Marvin the Martian sprung from the space-based antics of the charming and delightful cameo appearance by Walter Lantz’s Woody Woodpecker in the film. Some things that tend to back up my supposition are the uncanny (or perhaps not so uncanny, if my thesis holds water) resemblances between the two animated films:

• the story arc of the moonbound rocket within each cartoon,

• the manner in which the rockets are first “revealed,”

• the look/design of the two rockets,

• the appearance of the two rockets in flight through space,

• and so forth, all illustrated by the two rocket screengrabs below from the two shorts. For a detailed expansion on this theory, see my book Mars in the Movies: A History or my blog, Mars in the Movies: A History … Now with Endless Possibilities (specifically, this post about the 1948 introduction of Marvin the Martian in the short Haredevil Hare).

8-9. Speaking of Marvin the Martian, he was given the honor of being the official NASA launch patch for Spirit, one of the two hugely successful Mars Exploration Rovers that landed on the Red Planet in 2004. How cool is that?

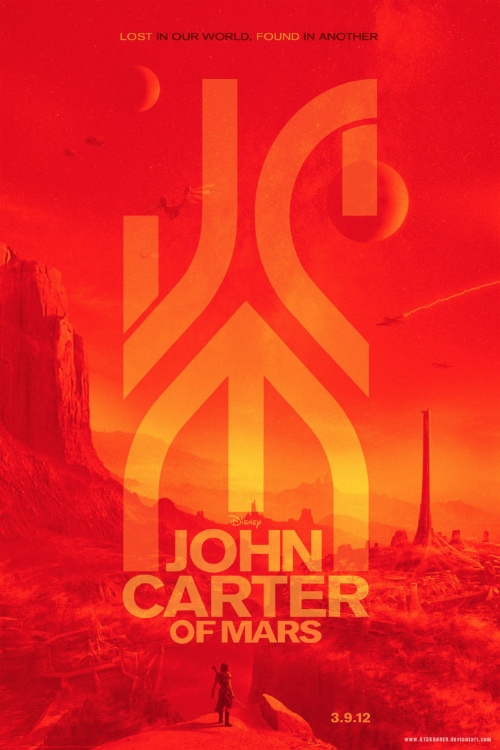

10. John Carter of Mars, as Andrew Stanton’s film was called early on, would have had some nice poster art — with a special graphic logo designed for branding purposes that would have been plastered far and wide if the film had been given a chance, but the $250 million movie was deliberately flushed down the toilet by the executives of its own company, according to Michael D. Sellers in his comprehensive John Carter and the Gods of Hollywood (Universal Media, 2012). Further, Disney had second thoughts about including “Mars” in the title because it had recently released a succession of movies with “Mars” in the title, none of which were especially successful, with one, Mars Needs Moms, being amongst the biggest money losers of all time, Thus, the movie was titled John Carter.

11. Science-fiction novelist and Star Trek veteran David Gerrold’s path intersected with the life of a bright little boy whose existence within the foster care system left something to be desired, so much so that the boy began to believe that he was a Martian, requiring umbrellas, sunglasses and all sorts of other aids to survive on this harsh planet earth. Gerrold decided that he must adopt the child, which he succeeded in doing, overcoming many challenges. He wrote a book about the experience titled Martian Child and it became a bio-movie with John Cusack (as Gerrold) and Amanda Peet. I would have liked to have written about the movie for my book, but since it didn’t include the planet Mars in any active way … I just plain ran out of time when my deadline loomed. I’ll include my thoughts on this most pleasant film at some point on my blog.

12-13. Nebo Zovot (The Heavens Call) was a wonderful 1959 science-fiction movie made in the then-Soviet Union. Apparently one point of its existence was to prove to the West that the USSR could make a movie every bit as good as the best of Hollywood’s output. Ironically, after the B-movie kingpin Roger Corman bought it and handed it over to the novice filmmaker Francis Ford Coppola with instructions to turn it into a movie for American teenagers, Coppola’s version, Battle Beyond the Sun (1963), did not hold a candle to the original. Left: an original Soviet one-sheet. Right: The German 2009 re-release poster. I find these simple but intense and colorful posters a delight. In fact, as I was writing the book, I used the Soviet poster on the left as my mock-up cover, it so touches on or reflects my hopes for my book.

14-15. Flash Gordon’s Trip to Mars (1938), with 15 chapters, was the middle of three Flash Gordon serials made in the 1930s. Once the serial had run its course, Universal Pictures recut the 300-minute serial down to a 68-minute theatrical feature named Mars Attacks the World. While the poster below for the serial (left) did appear in the book, I would have liked to have included the poster for the cut-down version as well. No time like the present!

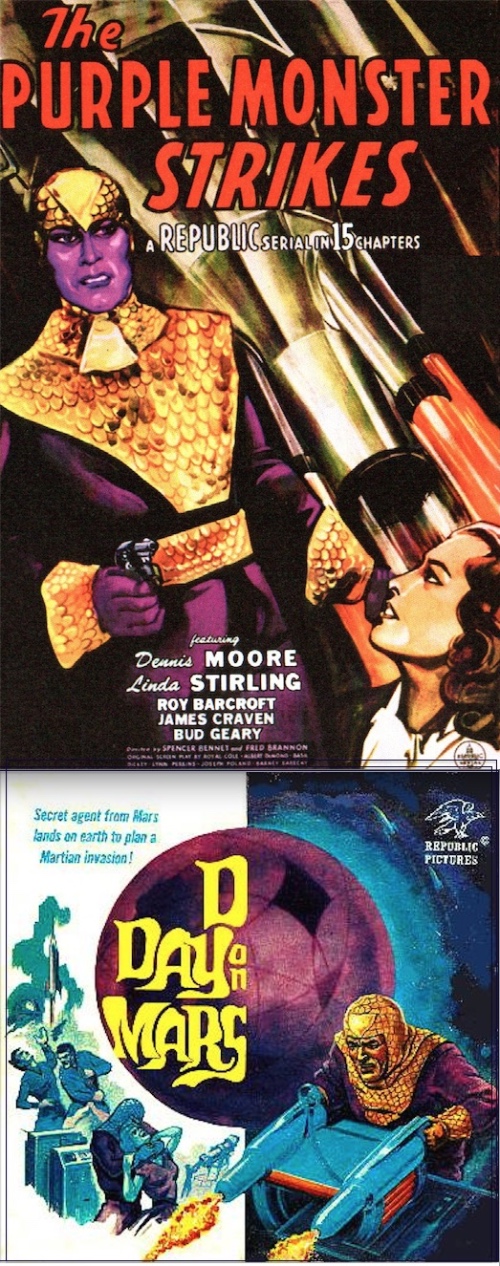

16-17. The Purple Monster Strikes (1945), with 15 chapters, was the first Mars-related serial to appear after Flash Gordon’s Trip to Mars (1938). In the beginning, we watch a tiny smear of light crossing the screen, the first words intoned are, “Out of the infinite distances beyond the stratosphere, a strange weird object is hurtling through interstellar space towards the earth.” That’s all well and good, but the object is a one-man spaceship from Mars, hardly from “infinite distances” or “interstellar space.” So, right off the bat we know that hyperbole and nonsense science rule this story. Once the serial had run its course, Republic Pictures recut the nearly 3.5-hour serial down to a 100-minute feature named D–Day on Mars.

18-19. Flying Disc Man from Mars (1950), with 12 chapters, came close to being a remake of The Purple Monster Strikes. Made five years afterwards, the opening sequences of Flying Disc Man from Mars are virtually identical with the same stock-shot one-man Mars craft crashing into a field with the same stock-shot Martian wearing the same costume hopping out before the craft explodes, just as a car with an inquisitive professional drives up with the same actor getting out and calmly greeting the Martian in much the same manner. In the previous movie, the Martian kills Dr. Cyrus Layton played by James Craven and takes over his body. This time Martian offers Dr. Bryant, also played by James Craven, an offer he can’t refuse. How would he like to take over the world, just as his hero Adolf Hitler would have if he’d had a better plan? Once Flying Disc Man from Mars had run its course, Republic recut the nearly 140-minute serial down to a 75-minute feature named Missile Monsters.

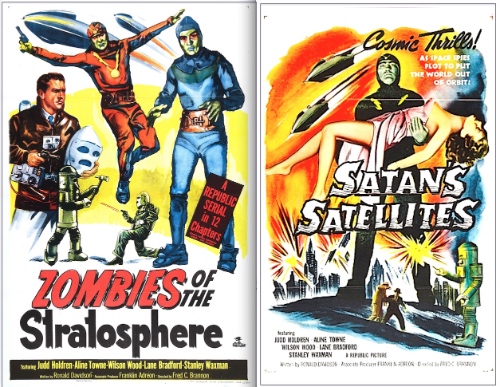

20-21. Zombies of the Stratosphere (1952), with 12 chapters, was the last of the Mars serials. Martians (aka zombies), scientists, and gangsters are in cahoots to use a super H-bomb to blow the earth out of its orbit to be replaced by Mars. Through all dozen chapters, Leonard Nimoy (yes, Mr. Spock himself) plays the Martian named Narab, who is the last Martian standing, so to speak. Once the serial had run its course, Republic Pictures recut the nearly 170-minute serial down to a 70-minute feature named Satan’s Satellites.

22. Nothing like a gooey, dripping, slimy, oozing, disintegrating-before-your-eyes, sickening-green Martian grasshopper to finish this round of coulda/woulda/shouldas from my Mars in the Movies: A History book! The big bug is from one of the three Mars movies I consider perfect, Five Million Years to Earth (UK title: Quatermass and the Pit). Not one frame is extraneous. Here is an excellent review: C.J. Henderson in The Encyclopedia of Science Fiction Films: From 1897 to the Present said, “Five Million Years to Earth is powerful, exciting, and intelligent … one of the high-water marks of science fiction. … Its formidably taut script is a masterpiece. There are no slow parts, no dragging scenes. Everything crackles with energy … one of the purest science fiction films ever made.” —Thomas Kent Miller

2-9, 12-21: special photo juxtapositions by Thomas Kent Miller, copyright © 2016-2017 by Thomas Kent Miller