All hu-mans, rejoice! Perhaps due to an error in calculation, someone has acquired the temerity to write an entire book about 1953’s Robot Monster, one of cinema’s legendary creative calamities. That someone is Anders Runestad, and that book is I Cannot, Yet I Must: The True Story of the Best Bad Monster Movie of All Time, Robot Monster. At nearly 700 pages, it tells all there is to be told of the film’s production and legacy, and here, in his Guest List for Flick Attack, Runestad tells us about his favorite films that — believe it or not — have ties to his book’s Golden Turkey classic.

All hu-mans, rejoice! Perhaps due to an error in calculation, someone has acquired the temerity to write an entire book about 1953’s Robot Monster, one of cinema’s legendary creative calamities. That someone is Anders Runestad, and that book is I Cannot, Yet I Must: The True Story of the Best Bad Monster Movie of All Time, Robot Monster. At nearly 700 pages, it tells all there is to be told of the film’s production and legacy, and here, in his Guest List for Flick Attack, Runestad tells us about his favorite films that — believe it or not — have ties to his book’s Golden Turkey classic.

Robot Monster in my view is the greatest bad monster movie of all time, and thereby an essential cult film of any kind, but why should this be the case when there are so many other contenders? Well, the contenders sadly lack a gorilla wearing a diving helmet who speaks to himself about his conflicted emotions.

It’s not really a diving helmet, of course. Familiarity with other science fiction films of the era shows a resemblance to the kind of helmets seen in Destination Moon (1950). But the urban legend of the movie being about a gorilla wearing a diving helmet never seems to die anymore than a good movie monster does, and that over-sized urban legend is the best way in which to sum up this bizarrely great and greatly bizarre experience.

What makes this monster so special? He’s a disturbing image of organic and mechanical conjoined, absurd, irrational, surreal, in a word — dreamlike.

So the best way to understand Robot Monster by way of comparison is to not so much compare it to other cheap monster movies, but to other mesmerizing and dreamlike cinematic experiences. For the surrealism of dreams can be funny, terrifying, beautiful, or just plain bewildering. With that in mind, here are five films that in one odd way or another connect to Robot Monster:

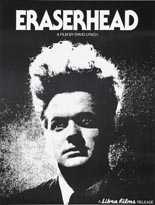

1. Eraserhead (1977)

1. Eraserhead (1977)

David Lynch’s debut is the cliché surrealist movie of recent decades, but that is only because it lives up to its reputation. In my book I Cannot, Yet I Must, I touch on how cheap monster movie directors sometimes without intending it did the same things that arty surrealists do. And Eraserhead shares with Robot Monster the sound of howling wind over an inhospitable landscape, physical abnormality, sequences that are difficult to fathom, and a self-destructive main character who can’t quite deal with all the demands being put upon him. And both films can seem alternately funny and horrifying.

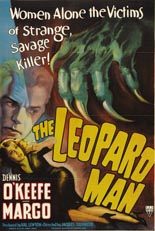

2. The Leopard Man (1943)

2. The Leopard Man (1943)

Speaking of horror, it is never appreciated enough how much horror often depends on the surreal. And for all of Robot Monster’s reputation as a ridiculous B movie, it commonly weirds out younger viewers. Among them was a young Joe Dante, who admits finding it then to be “surreal and scarifyingly bleak.” There are plenty of iconic examples of horror drawn from surreal effects (like Stanley Kubrick’s The Shining), but I’m especially drawn to Val Lewton and Jacques Tourneur’s The Leopard Man. Even among Lewton’s followers this is an often ignored example of the low-budget thrillers he produced, but it is one of his eeriest. The film never quite crosses the line into overt surrealism, but the irrational is always lurking and frequently invades the fabric of what seems possible. Set in a desert town with great atmosphere, it also features such Robot Monster motifs as a monster on the loose, a ravine, and (again) the mysterious sound of the wind.

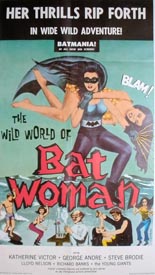

3. The Wild World of Batwoman! (1966)

3. The Wild World of Batwoman! (1966)

What happens when a comedy is not funny in the slightest? In the case of Jerry Warren’s no-budget attempt at cashing in on the Batman craze, it becomes an all-out assault of surrealist lunacy. Warren’s movies are mostly not that great (reportedly because he wanted to save time and money by making them badly on purpose) while also not that entertaining in all the wrong ways. Batwoman is a major exception, as one attempt at humor after another falls flat, in combination with a nonsense storyline and a menagerie of bizarre characters whose purpose in the story is not always clear. The truly surreal thing is that it is supposed to be funny while it is not funny at all, and yet it is funny because the fact that it was meant to be funny makes it hilarious on another level entirely. And that makes it almost as odd as the monster’s introspective speeches in Robot Monster.

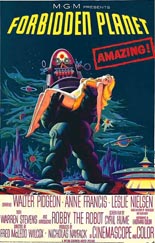

4. Forbidden Planet (1956)

4. Forbidden Planet (1956)

The only color film on this list demonstrates how a ’50s monster movie plays when done on a big budget with a good script. Many of the same tropes of other such films are here, while they are given the treatment that all makers of movies like Robot Monster wished could have been theirs. Forbidden Planet has a mystery at its center, and the power of the dreamlike image manifests itself over and over. The movie’s beloved Robby the Robot even looks much like how Robot Monster was intended to look in the script before becoming a gorilla wearing a diving helmet on screen for budgetary reasons.

5. The Beast of Yucca Flats (1961)

5. The Beast of Yucca Flats (1961)

And this list closes with a movie that, like Robot Monster, puts all aspects of the surreal together in an amazing no-budget package. The opening sequence is horrifying in content while ridiculous in execution, and the remainder just gets weirder as Tor Johnson wanders around the southern California desert attacking people while an omniscient narrator drones on about a flag on the moon, thirsty pigs, and characters who are caught in the wheels of progress. It is difficult to know if director and actor Coleman Francis had some serious idea behind the strange, haiku-like narration he recites over the endless landscapes of this movie, or if he just had to connect all the footage somehow and unleashed his unconscious poetic side without intending it. Phil Tucker, Robot Monster’s director, was a practical and hardworking guy who became a very talented editor, and did not intend anything but an exploitable low-budget monster movie. So I don’t want to assume anything about Francis’ intentions with The Beast of Yucca Flats. But it doesn’t, in the end, matter all that much. As has been said before by others: Trust the tale, not the teller. —Anders Runestad