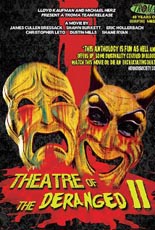

Just as few things in life bring me more pleasure than a good horror anthology, there are few things in life I loathe more than a bad one. And Theatre of the Deranged II is wretched.

Just as few things in life bring me more pleasure than a good horror anthology, there are few things in life I loathe more than a bad one. And Theatre of the Deranged II is wretched.

Hosted by Internet-famous psychic ghost hunter Damien Shadows (actually wig-wearing ringleader Eric Hollerbach), this sequel to the 2012 obscurity presents five stories of “blood curling” terror, all supposedly full of “audiovisual conjuring spells.” After each, Mr. Shadows explains — in leaden, dreadfully unfunny skits — how to combat the evil to which viewers have just been exposed. If that truly were the case, this Deranged project would cease to exist.

The movie doesn’t work because … well, for myriad reasons, but notably because the tales come from such disparate directors whose DIY visions form no satisfactory cohesion, collectively or (with one exception) individually. As a whole, their approaches lean toward the comedic roughly as much as the horrific; the effect is reminiscent of channel surfing, and almost every choice seethes with regret.

For example, Shane Ryan, the man behind the infamous Amateur Porn Star Killer trilogy, contributes the opener, “Tag,” a pretentious and bloody anti-narrative that would be baffling even if its two women weren’t speaking in Japanese. Next is Shawn Burkett’s sorority-house slasher send-up, “Panty Raid,” a juvenile exercise in stupidity in which the killer rids the campus of one unaware coed by kicking her sex toy into her as she’s pleasuring herself with it. “Tag” flows into “Panty Raid” as well as an 80-year-woman driving a Lincoln Town Car does with freeway traffic at rush hour, yet the shorts would be unbearable standing alone, too.

For example, Shane Ryan, the man behind the infamous Amateur Porn Star Killer trilogy, contributes the opener, “Tag,” a pretentious and bloody anti-narrative that would be baffling even if its two women weren’t speaking in Japanese. Next is Shawn Burkett’s sorority-house slasher send-up, “Panty Raid,” a juvenile exercise in stupidity in which the killer rids the campus of one unaware coed by kicking her sex toy into her as she’s pleasuring herself with it. “Tag” flows into “Panty Raid” as well as an 80-year-woman driving a Lincoln Town Car does with freeway traffic at rush hour, yet the shorts would be unbearable standing alone, too.

The anomaly of Theatre of the Deranged II — yes, one exists! — is My Pure Joy director James Cullen Bressack’s “Unmimely Desire.” Although it’s too long, the segment possesses what the other pieces do not: achievement. In this case, we’re talking genuine laughs. After all, when’s the last time you saw a mime murder people with his invisible weaponry? It’s inventive and clever, yet made on the same nonexistent budget as those surrounding it. Whether he realized it or not, Bressack proves that good ideas don’t necessarily need big bucks to be pulled off. But without that funding, bad ideas look even more hopeless. —Rod Lott